The professional community has been aware for years of the weakness and lack of protection it suffers, mainly due to a lack of legislation, but also to the lack of social recognition, professional intrusion and job insecurity. Nonetheless, it was necessary to undertake a careful analysis with objective data—and a collaboration between this group and the public administration offered a good opportunity to do so.

In 2018 the society Associated Conservators and Restorers of Catalonia (CRAC) commissioned a study on the sector to independent consultant Margarida Loran, who accepted the project. Its planification conceived three different phases: a preliminary study (2018), a research phase (2019), and a strategic reflection phase (2020).

The preliminary study, carried out in 2018 and funded by the Barcelona Provincial Council, is entitled “Problems of the Conservation-Restoration Sector in Catalonia”. This study includes a revision of previous works on the subject, exploratory meetings with the CRAC board, and ten in-depth interviews. All this establishes the sector’s context and identifies its main problems, challenges, and possible solutions.

The research and strategic reflection phases, funded by the Government of Catalonia, were summarized in the document “Study on the Current State of the Conservation-Restoration Sector in Catalonia 2019”. The aim of this work was to collect data and evidence that supported the problems identified in the preliminary study, contextualizing the sector and facilitating the understanding of its needs. During the research phase, exploratory meetings were held with key agents in the sector;(1) visits and interviews with five specialized Conservation-Restoration (C-R) centers; the reviewing of existing indicators and data; a questionnaire aimed at curators-restorers and a second questionnaire aimed at museums, archives and C-R centers. During the following phase of strategic reflection, three critical issues were addressed with focus groups. Thereafter, the results of all three phases were disclosed in order to bring the sector’s status and future challenges to light.Overall, this is a very comprehensive and rigorous study that combines qualitative analysis (interviews, visits, and focus groups) with quantitative analysis (statistics reviewing, training indicators, and questionnaires). It was an ambitious and strategic project for the CRAC, and a great effort made over two years, which achieved a clear involvement of the sector. Both the association’s board of directors and the independent consultant who carried out the study are convinced that it will be of great relevance to the C-R professional community and to the heritage field in general. The summary document of the study is available on the CRAC website, as well as its presentation, which took place on 7 October 2021 at the Palau Marc.

2. The exploratory phase. Preliminary study. Problems of the sector

In order to center this study, first of all it is essential to define what do we mean by “conservator-restorer”. A conservator-restorer is a professional who acts on tangible cultural heritage—movable property, real estate decorative elements, and furniture incorporated into real estate—with the goal of preserving it for present and future generations. They have the training, knowledge, skills and experience required for the exercise of the profession of conservation-restoration.(2)

The reviewing and analysis of existing documentation, as well as in-depth interviews, make it possible to identify the problems of the sector and the profession in Catalonia. The selection of the ten experts to be interviewed aims to capture different perspectives, areas of activity and specialties, gathering opinions from academia, specialized centers and museums, freelancers, companies and associations.(3)

The analysis of all ideas and opinions, all of them free and subjective, helps to determine five main structural problems and challenges for the C-R sector in Catalonia.

2.1. Lack of social recognition

In general, there is a great deal of ignorance about the methods and competencies of C-R. Despite its vital role in preserving cultural heritage, it is a little-known and little-recognized activity. This translates into unfavorable working conditions, professional intrusion—which poses a risk to heritage—and insufficient public policies and budgets.

2.2. Lack of legislation governing the professionThe regulation of the profession is the cornerstone of all the problems in the sector, and the focus of the struggle of many associations. The figure of the conservator-restorer does not appear in the Catalan Cultural Heritage Act (1993). The consequences of this absence are many, such as the almost non-existent presence in decision-making positions (advisory boards, expert commissions and heritage inspection tasks), the inferiority of the status of the C-R with respect to other heritage professions (which end up invading C-R's own competencies), or the impossibility of objectively measuring the quality of C-R's work.

2.3. Duplicate, disordered and non-homogeneous formationCurrently, there are two training routes to obtain the C-R degree in Catalonia: The Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona and ESCRBCC. Graduate studies and irregular training proposals proliferate, but there are specialties that are not covered and have both demand and potential for the future. Therefore, there is a high number of graduates for the reality of the job market.

2.4. Deficit of C-R in heritage institutionsIt should be noted that there is a context of poor management of collections in general, but the role of C-R always draws the shorter stick. Few museums have stable C-R staff teams, and those that do, tend to reduce them. The C-R is mostly outsourced, and in many cases discontinuously. Specialized support services(4) either don’t suffice to cover the needs of the whole territory or are non-existent.

2.5. Professional activity in adverse conditions

On the one hand, the reality of the C-R sector is a set of microenterprises and self-employed professionals working mainly for the public sector. It should be noted that in public practice, there are very few permanent jobs, and there has been a stagnation of jobs for years. On the other hand, private practice is fraught with difficulties as a result of recruitment problems and bad practice in outsourcing, which leads to a precarious job market.

Several factors are endangering the sector: restrictive contracting legislation that suffocates freelancers and small businesses, the context of job instability, insufficient budget for heritage conservation, the predominance of the price criteria in tenders and the lack of legal regulation on the figure of the C-R.

Some examples can be seen in the architectural projects in which a very unequal relationship is established in comparison to constructors and architects (C-R is relegated to a marginal and subordinate role), as well as in exhibition projects with a lack of integration of the C-R from the beginning, although it is essential for the preventive conservation of the goods on display.

Once the sectoral difficulties have been identified and exposed, consultant Margarida Loran relates these intricate problems to their challenges and possible solutions or proposals, which were also extracted from the questions asked to our interviewees.(5)

In conclusion, in this preliminary study the complex reality of the sector is made clear, and many shortcomings are identified, some of which are very serious. However, despite this context of many difficulties in the relationship towards the public sector, there seems to be a positive trend towards greater awareness in heritage institutions, especially regarding preventive conservation.

3. Analysis of the sector. Key results of the current situation

The second phase, the research phase, is conducted in 2019 and provides objective evidence on hot topics identified in the preliminary study. As mentioned above, all data are obtained, on the one hand, from meetings, visits, and the reviewing of existing indicators—and on the other hand, from collecting information and opinions through two electronic questionnaires:

—One, aimed at conservators-restorers, which received 414 responses. It is not possible to know which percentage of the whole sector this number represents, because there is no census of professionals, but an attempt was made to reach the maximum number of people.(6)

—The other, aimed at heritage centers and specialized services, which obtained 132 responses, distributed as follows: 48% museums, 45% archives, and 8% specialized services and national institutions.(7)

The key results of the research are listed below.

3.1. Employment and work situation

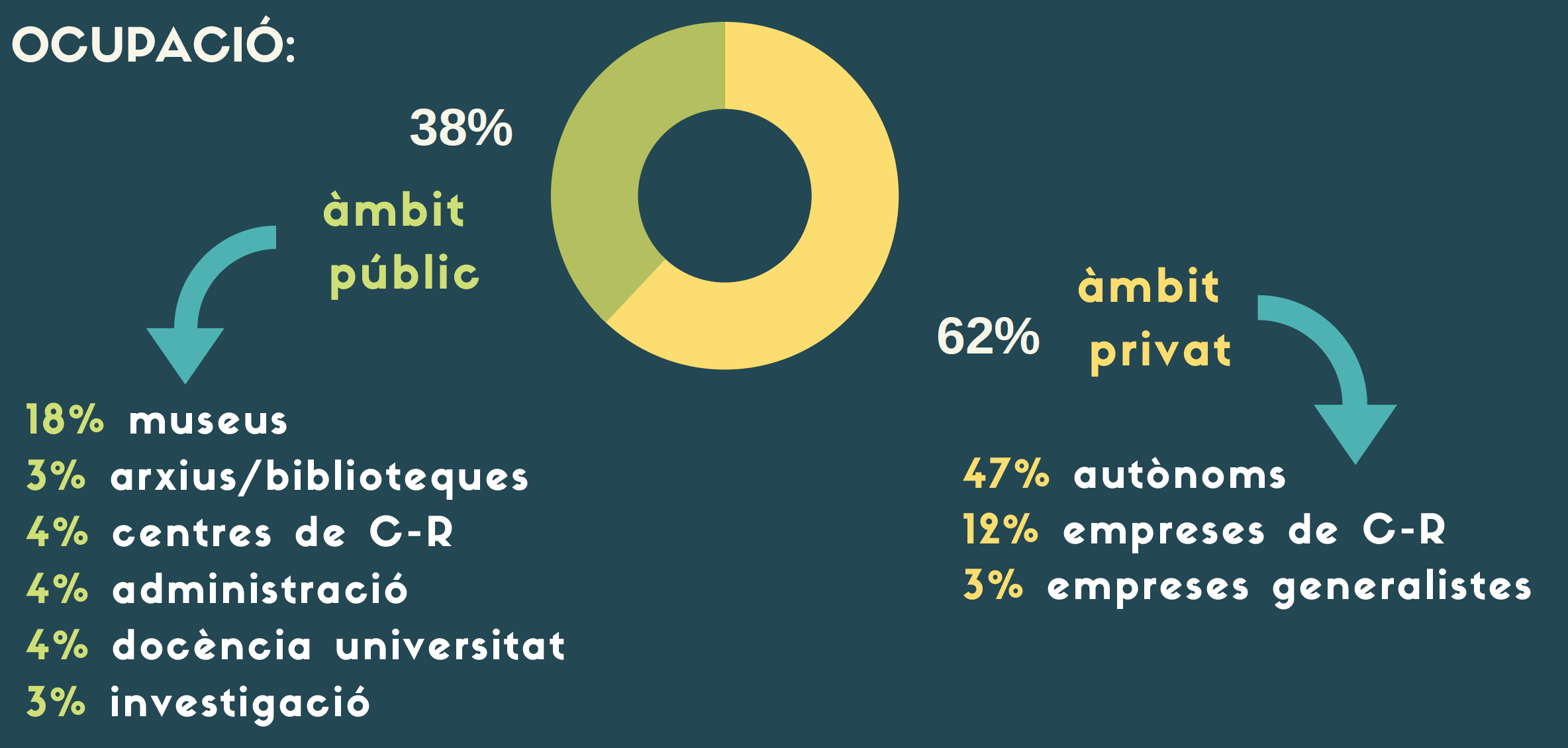

Nearly two-thirds of all active professionals work in private practice (62% of the employed respondents), and the other 38% in the public sector.

It should be noted that the percentage of freelancers is 47%, and it is even higher (49%) when asked about the combination of self-employment with other kinds of occupation, because it is not uncommon to combine both options.(8)

If we take into account the total number of professionals surveyed, more than a quarter are in a work situation that is not fully active or not fully dedicated to C-R.(9)

Regarding the type of contract, only 28% of those who are self-employed have a fixed or indefinite contract. Of these, those with more years of experience predominate (71% have more than 16 years of experience).

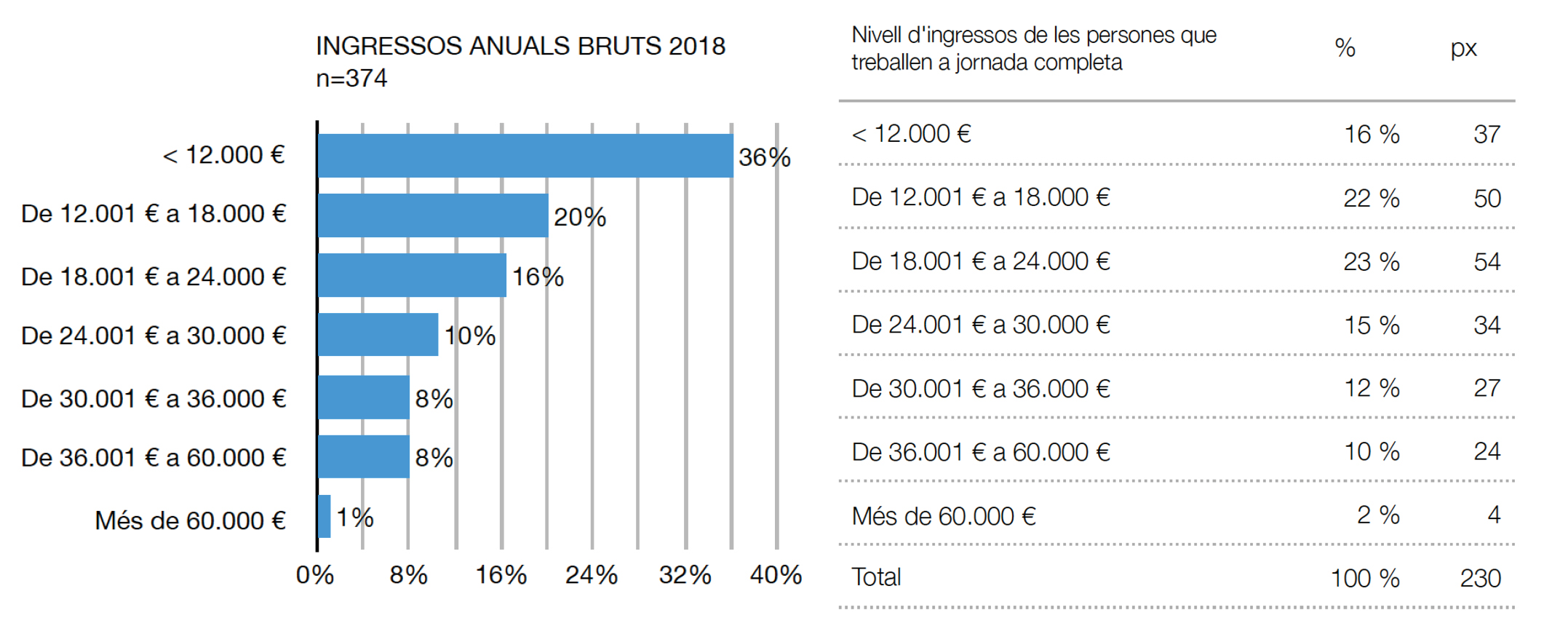

3.2. Annual gross wages or incomeMore than half of the surveyed professionals (56%) do not exceed a gross income of 18,000 euros per year with their C-R work, far from the average annual gross salary in Catalonia (25,180 euros in 2017, according to Idescat), and even further from the average gross salary of scientific and intellectual professionals (34,129 euros in 2017, according to Idescat). Only 17% of respondents exceed 30,000 euros.

In terms of time dedicated to work, there is a high percentage of professionals who work part-time (temporary work is another trait of the sector, which means more precariousness, as well as the need to combine C-R activity with other occupations).

However, it is alarming that 38% of those who work full time do not earn more than 18,000 euros, and that the most common income bracket among them is 18,000 to 24,000 euros, still below average salary in Catalonia and far from that corresponding to a professional with a university degree.

If we cross this variable with employment, the lowest levels of income are in private practice, which as we have seen is the major group of employment (87% of those working in companies and 82% of freelancers earn less than 24,000 euros). The highest salary levels are among those who work in heritage centers and, therefore, receive a closer figure to the Catalan average (76% above 24,000 euros and a half above 30,000 euros).

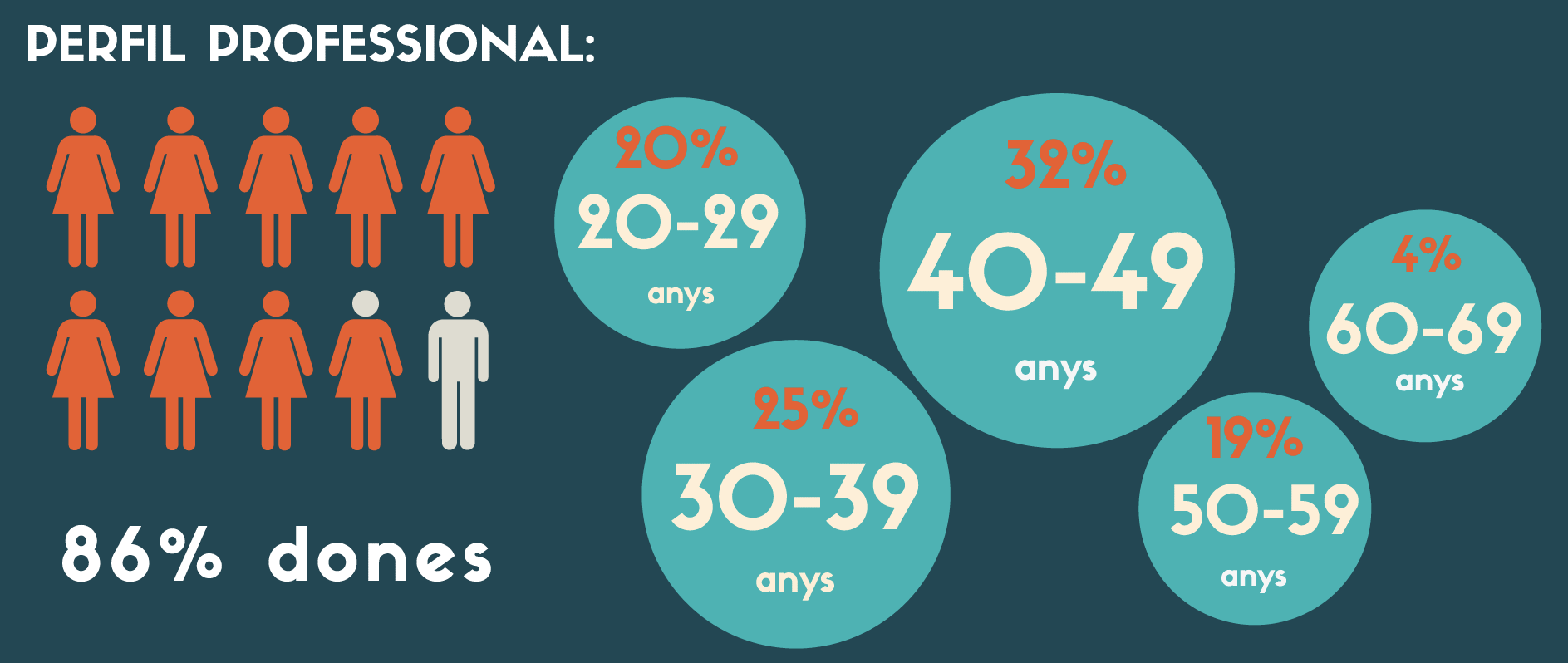

3.3. Professionals profileOne could say that C-R professionals are relatively young and mostly feminine (86% women). The results show a balanced age structure, not aged at all, with professionals covering all ranges, but with more representation of those whose profession is consolidating (57% are in the 30-49 years old group).

Most of respondents live in the area of Barcelona (three quarters of them), and the working area of the majority is Catalonia (89%), although 15% also travel and work in other territories (Spain, Europe, or the further out).

3.4. Formation. Official entry-level trainingUntil now, the training requirement for entry into the profession has been considered to be official undergraduate studies. The two institutions that currently offer these in Catalonia(10) together produce a very high number of graduates per year compared to the reality of the job market. The profession grows with an average number of 59 graduates each year. Between 2011 and 2018 a total of 402 students graduated.

Master’s studies are expected to become an entry-level training requirement in the near future, as recommended by the European Network for Conservation-Restoration Education (ENCoRE). However, currently in Catalonia the offer of specific C-R master's degrees is limited—only two are offered.(11)

Internships and scholarships

Several Catalan heritage centers specializing in C-R offer internships for students and scholarships for graduates. Although the offer of internships is wide—the Center for the Restoration of Movable Property of Catalonia alone welcomed eighteen students in 2018—, the offer of scholarships is more limited—nineteen annual scholarships offered by five centers.

Training attainment of professionals and continuous trainingThe general training level of the sector is high, as 34% of professionals have master's- or postgraduate-level studies. In terms of specific C-R training, most professionals completed official studies at the undergraduate level (87%), but only 17% obtained a master's degree in C-R.

The sector is committed to continuous training (78% have taken at least one specialized 20-hours-long course or more in the last two years). The commitment to updating knowledge is firm throughout their whole professional life, as this percentage remains high at all ranges of experience, which is a very positive indicator for the profession.

It should be noted that these data on the level of education contrast with those on the low level of income throughout the sector. This fact is surprising, and it highlights the serious problem of low professional recognition in the sector.

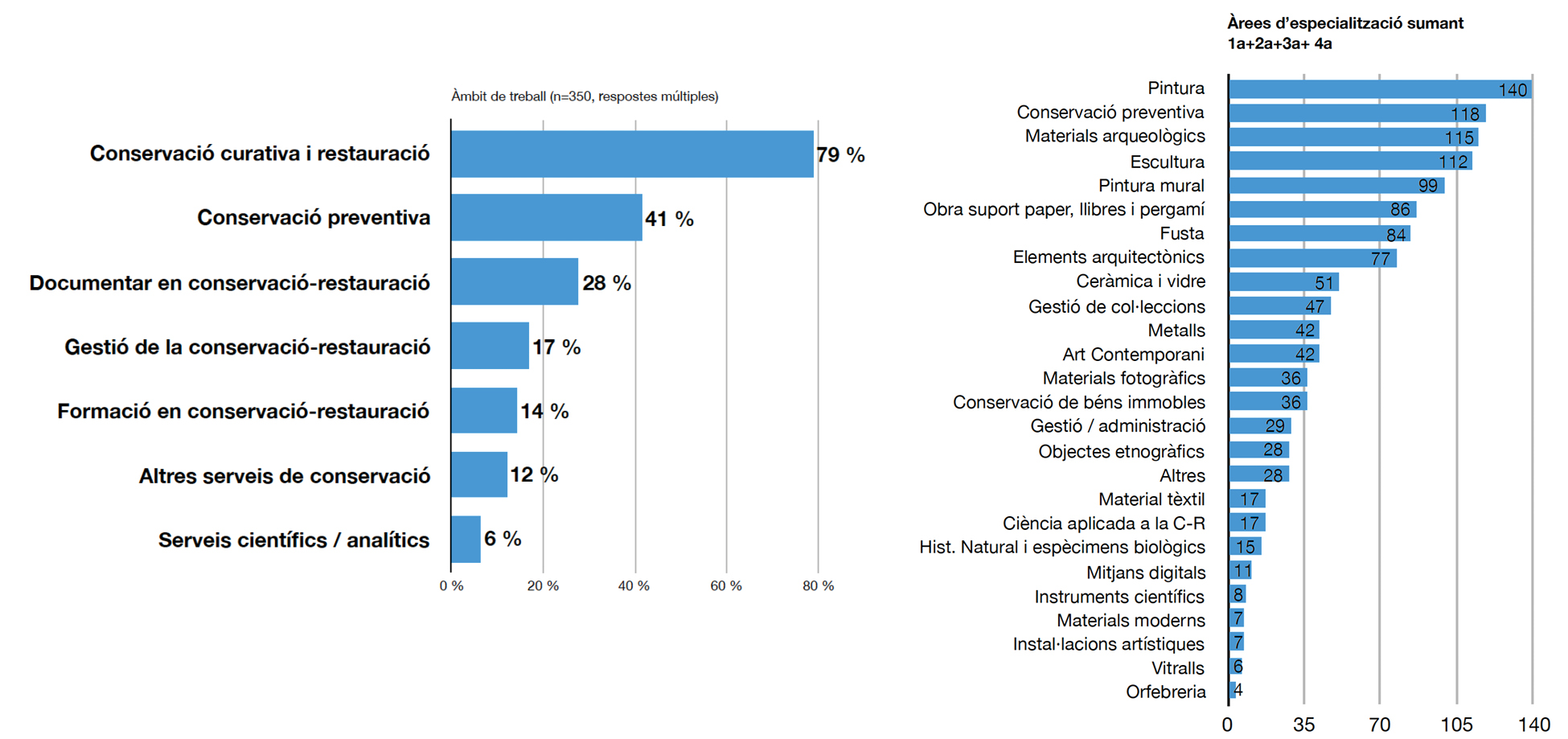

3.5. Work and specialization areasProfessional practice and training offer are very much focused on the curative conservation and restoration of a few “traditional” specialties. It is clear that preventive conservation is making inroads, but it is still far from being a practice for the whole community.

The main areas of specialization (respondents could select 1st specialization, 2nd, 3rd and 4th) are closely related to the training taken and the market demand. Dominant specializations clearly are painting (almost a quarter of respondents), graphic documents, and archaeological material. Sculpture, wood and preventive conservation come in as secondary. Thereafter, there is a long series of largely minority specializations considered “non-traditional” and not included in the current formative offer. Some are not much or not at all covered by professionals, e.g. stained glass, textiles, goldsmithery, scientific instruments, or art installations. There is a significant gap in expertise in these minority specializations.(12)

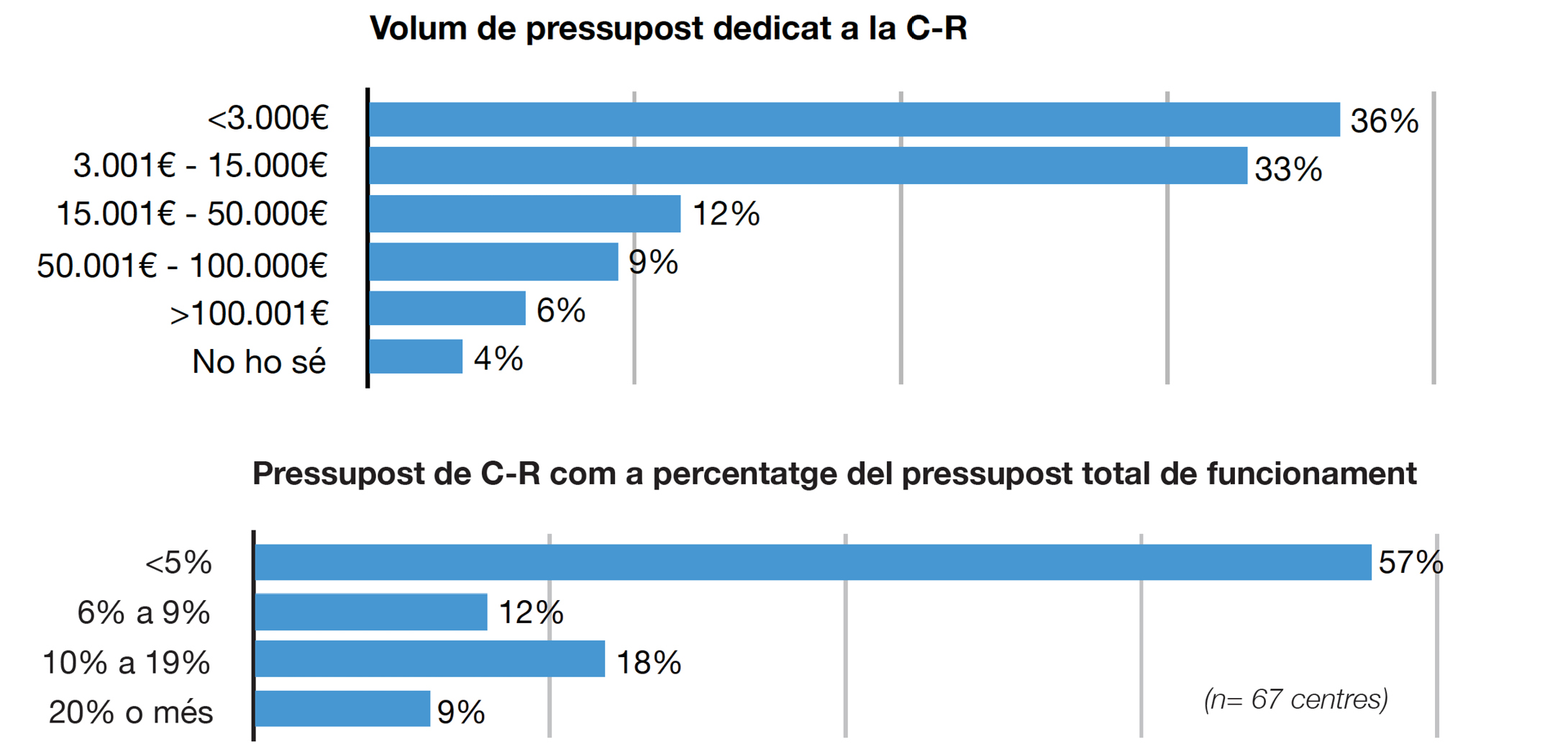

3.6. Conservation-restoration in heritage centers. Budget

More than half of the centers that answered our questions(13) have a budget dedicated to C-R (or have it planned for the future). However, it is disturbing that a third do not have it, given that all of them hold heritage assets (in archives, this percentage is even higher and reaches 41%). The volume of this budget in 36% of all cases is almost symbolic—less than 3,000 euros, which is a very widespread situation, especially in the case of archives. If we compare these budget lines with the total of the operating budget of these centers, in most cases it is less than 5%.

Despite this percentage being so low, almost half of the centers indicate that they have seen an increase of the economic resources devoted to C-R compared to ten years ago, in the midst of the economic crisis.

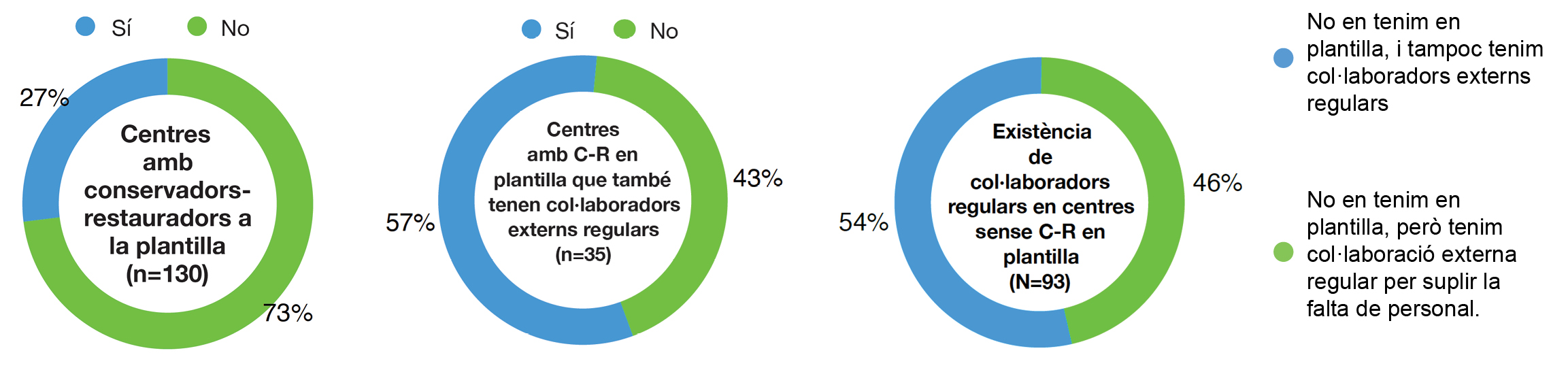

StaffAlthough there is a clear shortage of C-R staff in heritage centers, this budget increase has not translated into hiring specialized staff. But the need for their services still exists, and therefore there is a great dependence on external professionals to cover knowledge and skills deficit in this area.

Only a third of all public centers have a C-R service (laboratory, workshop or program), and only in 19% of all cases this service is internal, not dependent on external support. Stable C-R staff teams are micro or unipersonal—almost half of the public centers that do have staffed C-R personal have only one employee—and there is no prospect for growth. We see a clear stagnation in the last ten years.

In other words, 73% of the centers do not have C-R personnel in their staff, and those who do need regular external collaborators, as their staff is insufficient for the workload to be satisfied.

Centers state that they have more expertise in aspects of maintenance and handling of collections (40% say so) than in conservation-restoration interventions (only 21% state that they have enough).

OutsourcingThe external conservation services used the most by centers consist of independent or freelance professionals. Generalist companies—which are seen as a threat in the current public procurement system—were only used on 2% of all occasions. It should be noted, however, that these data are prior to the Public Procurement Act (in force since March 2018) and that the picture may have changed. This is a concern that was raised in the interviews during the preliminary study.

3.7. Outsourcing C-R servicesWe wanted to test whether the new Public Procurement Act has a negative impact on the ability of professionals and companies in the sector to tender for public projects or to provide outsourced services.

When asking professionals in private practice, at the moment it was not possible to clearly establish whether the amount of work that they do for the administration through tenders has changed (the data were collected in 2019 and the law is from 2018).

If we consider the perception of all the surveyed professionals—both those who work in the private and public spheres—83% totally agree or agree that the current context benefits the large generalist companies of services and harms self-employed and companies specializing in C-R, putting the model of the sector at risk, and that small C-R companies often end up being subcontracted by large companies outside the sector (from the construction or the services sectors). 79% fully agree or agree that it is difficult to compete in public tenders due to the difficulty of meeting the required economic and/or technical solvency requirements.

When asking centers, 15% indicate a change in the type of external service they used in the last five years (in museums, the percentage rises to 23%). So, maybe there is a tendency for change that is yet to become widespread. There is also a perception in public centers that the new law makes it more difficult to hire freelancers on a regular basis, and that outsourcing is changing in favor of generalist companies that are more competitive pricewise and meet the economic requirements of the law.

As far as outsourcing practices are concerned, it is key to define the technical requirements in the tender documents properly, because this is the way to counter the tendency of the administration to make the lowest price prevail. In more than a third of the centers that have answered our questionnaire, the person who prepares these specifications does not have training nor experience in C-R (in archives it exceeds 50%), and this is an alarming fact, as this is considered a basic condition for quality outsourcing.

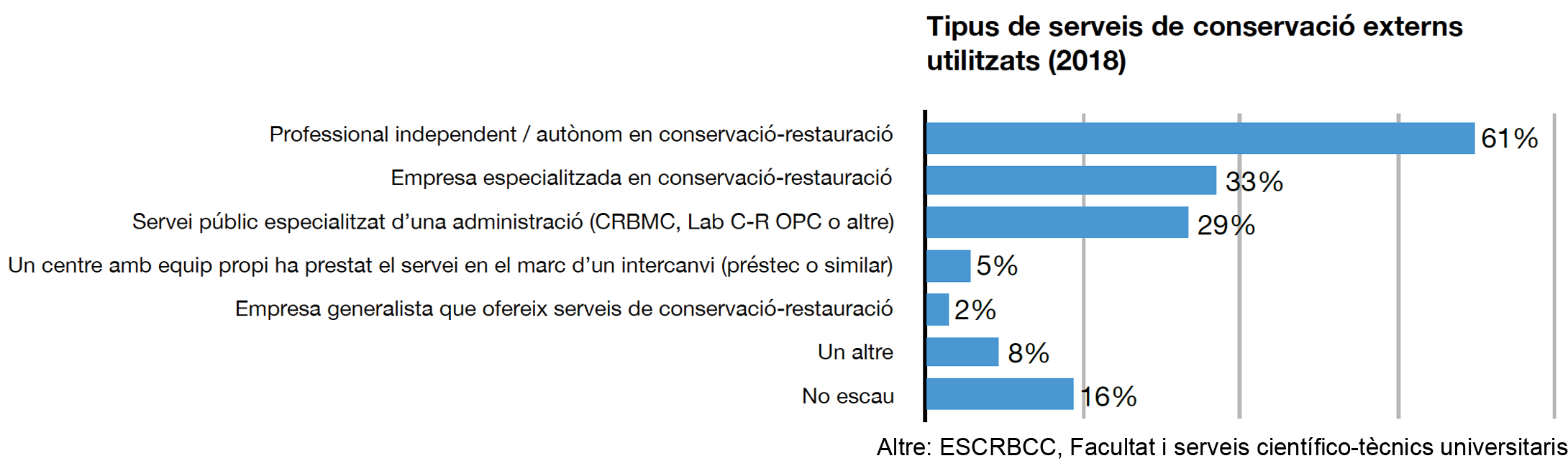

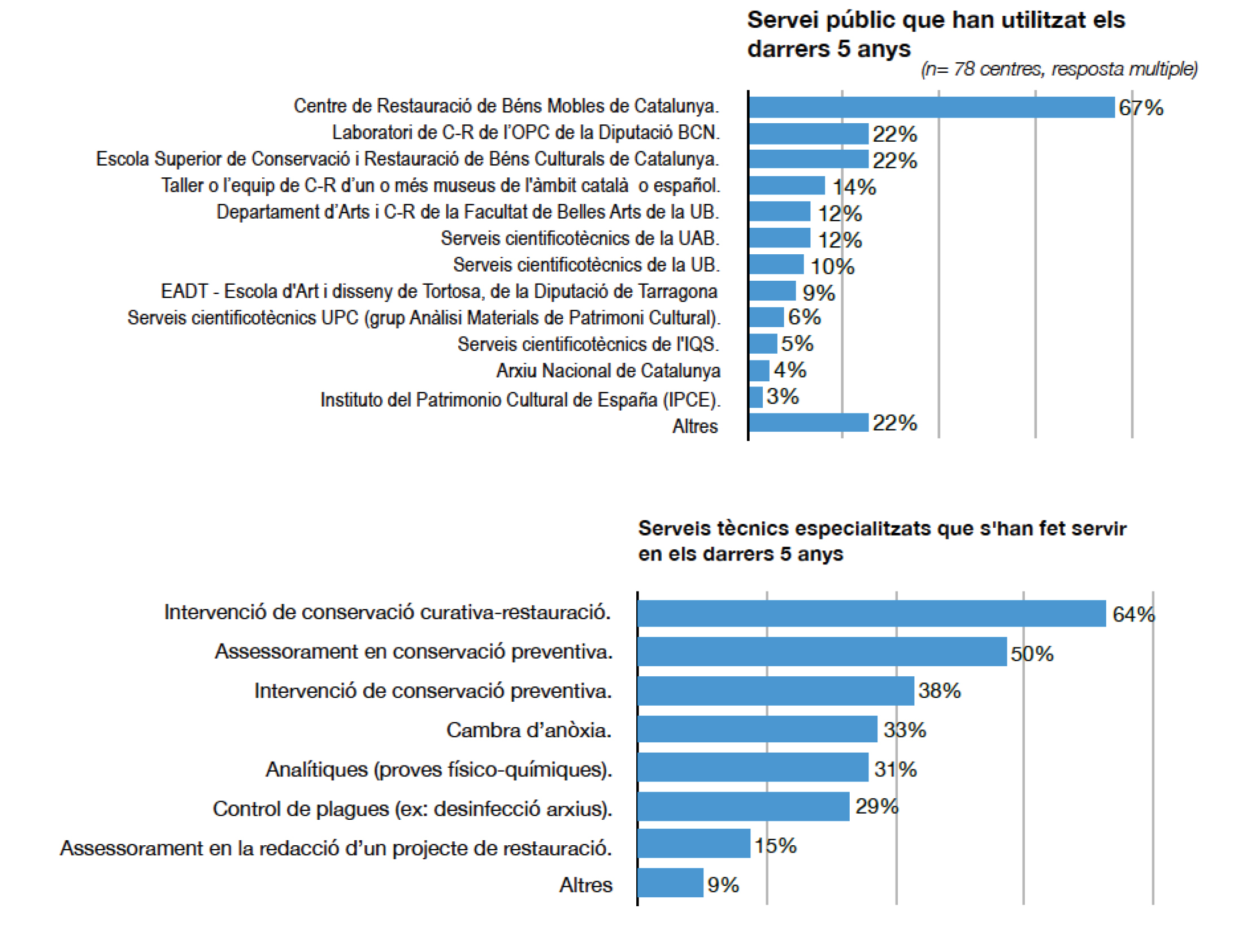

3.8. Use and relationship to specialized public servicesThe most widely used specialized service is by far the Center for the Restoration of Movable Property of Catalonia (CRBMC), and this reflects its role as a reference center. Half of the individual professionals have collaborated, worked or trained there in the last two years, and two-thirds of all centers have used their services.

Among individual professionals, almost half of them have also collaborated with the C-R team of one or more museums, a little over a third with ESCRBCC and a quarter with the Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona.

Among the centers that have never used a specialized public service, the most common reason is ignorance of the procedures for requesting it, as 36% are unaware of its existence. Other reasons include: a type of heritage that does not have access to it (ethnological material), the awareness of the saturation of centers, and the lack of budget to assume 50% of the expenditure.

4. Reflections and recommendations on three hot topicsThree debate groups were organized in January and February 2020, with professionals in the sector of various profiles representing all perspectives.(14) The focus was on three issues that are considered critical and that the sector needs to address. Each group reflected on their results and generated recommendations and consensual proposals.

4.1. Official training. A horizon for change

There is a clear recognition of the problems generated by duplication in official training, heterogeneity in acquired skills and training decompensation in specialties. The strength of the data requires action. It is also recognized that unified training would strengthen the sector.

So, how do we face the great challenge of unification?

Although the current regulatory framework does not facilitate this, now there is a more favorable political context than in the past, and forces for change are identifiable. It is necessary to find a formula to add and not lose, that is, to concentrate and to maintain resources. There is a willingness to jointly seek a solution for the future. Different agents are willing to take steps in that direction.

Among the agreements:

—The non-absorption of one institution by another, but the construction of a third model.

—A new model located in the university environment.(15)

—Agreements, consortiums or alliances with the scientific-technical field.

—A five-year-long curriculum of specific training in C-R (degree with integrated master's degree 2+3 or 3+2). Two years of general training, then introducing specialties in the 3rd year.

—A new curriculum with a solid basis of scientific-technical knowledge and preventive conservation from the beginning for all specialties.

—The resolution of the duplication of specialties and the offer for those that are not covered.

—Facilitating homogeneous skills for all graduates.

It is also agreed that the challenge of continuous and complementary training should also be discussed and addressed in order to adjust to the needs of the sector and to avoid professional intrusion. Official training institutions have an important role to play in this, collaborating to support, monitor and validate.

4.2. Specialties. Deficits and opportunities

Professionals with responsibilities or expertise in poorly covered specialties all agree that the current landscape, which includes just a few “traditional” specialties (painting, sculpture, archeological assets and graphic material), does not fit into the much more plural reality of C-R. There are many minority specialties without visibility, training, or experienced professionals. It is well-known that including these new specialties would help expanding and professionalizing the sector, distributing job opportunities and gaining recognition to combat misunderstanding, both inside and outside the profession.

There are plenty potential forces for change, like the possibility of including these specialties in future new curricula or the growing trend of preventive conservation and scientific analysis. Furthermore, there are reference centers that already have expertise in these poorly covered specialties—contemporary art, industrial heritage, film heritage, and so on. On the other hand, there is also the challenge of maintaining the existing expertise in "traditional" specialties in specialized centers and expanding them, because the teams working on them are still too small.

So, how do we face the great challenge of inclusion?

Among the agreements:

—Strengthening the public system by incorporating reference centers and laboratories in these specialties and materials, which, beyond their own tasks, have a lot of potential to serve our territory.

—Creating a “network of centers” and committing to sharing knowledge (under the CRBMC’s leadership but with delegated responsibilities).

—Specific training for a small number of students in collaboration with reference centers for each specialty, reinforcing scientific knowledge.

—Prioritizing the development of scientific conservation, which is solidly established in other countries but has hardly any experts or services in Catalonia.

—Promoting the indispensable collaboration with other professions (engineers, photographers, and so on). It is necessary to incorporate trainers and students from other fields so that the new specialties are developed in a multidisciplinary space.

4.3. Outsourcing. Towards a quality practiceBoth the representatives of institutions that outsource and the professionals who work for the public sector recognize the results of this study in this matter—the problem of the low presence of C-R in the stable teams of cultural centers and the high degree of C-R outsourcing (either punctual or regular), which comes from problems linked to the administration. The perception of a lack of transparency and real openness in procurement is also expressed.

It is agreed that outsourcing will continue for years, and therefore it is an urgent priority to apply good practices so that our outsourcing is of the highest quality. There is an awareness that this is a common challenge with other sectors within the cultural field.

So, how do we face the great challenge of quality outsourcing?

Among the reflections and recommendations that arise:

—Heritage centers need support, guidelines and training for the people who elaborate tender documents.

—The main agents in the sector(16) are asked to inspect the recruitment processes and to defend the right of C-R workers to direct projects of immovable heritage.

—The CRAC is asked to study pricing recommendations for outsourcing, as well as to promote awareness that preliminary studies (diagnosis) are part of orders and should be paid for (study+intervention).

—Preventive conservation should not be outsourced—it should be integrated as an internal function.

—The idea arose to open the use of C-R laboratories in public centers that are currently underused as work centers for independent professionals or specialized companies, which would help them reduce costs.

—The CRBMC, as the head of the public system channeling funding and carrying out interventions with external collaboration, is asked to: display more pro-activity in communicating services and their ability to help; showing more transparency and openness; strengthening the role of reference center (leadership of complex projects, provision of cutting-edge services such as scientific conservation); reducing services that can compete with freelancers and small businesses, and updating to better respond to the needs of the sector.

5. Conclusions. Conservation-restoration: a profession of the future?

Margarida Loran concluded that C-R is currently “a growing profession, with a well-trained group, but which is developing through a lot of obstacles and shortcomings. . . The low level of income and the precariousness of a significant part of the professional community are alarming”.

It should be noted that awareness of the fact that it is a highly feminized profession is possibly contributing to low social recognition, low income and precariousness (independent, temporary and part-time work, among others), and it is urgent and necessary to address this issue.

It is confirmed that the resources of C-R in museums, archives and specialized centers are deficient and disturbing, as these actors are responsible for the custody of heritage assets. But the lack of human resources is even worse than the lack of funds, as stable staffed teams are an exception, not the norm. The low presence of C-R in stable teams means that they are left outside the decision-making process that affects cultural heritage.

This study shed light on endemic issues in the industry and provided with a solid foundation on which we should work on. There are critical needs and issues that the sector needs to address. That is why we call on all actors, from political leaders, training centers, heritage centers and specialized services to associations, professionals and companies, for all these ideas to be understood, developed and accomplished.

It is clear that the biggest challenge, the most important and urgent one, is the legal regulation of the profession—to obtain recognition and guarantees—and some initiatives have been set in motion in this regard.(17) In the training field, the challenge is to unify and improve the formative offer and to reduce the number of graduates who come out each year, one of the main lines for facilitating the regulation of access to the profession. It is necessary to consolidate the professional figure and to improve the job market, achieving the application of good practices in outsourcing.

In order to achieve this, it is essential to make society aware of the profession and the conservation of heritage—a great task of visibility and dissemination is in order. The practice of C-R has particularities that must be visible and defended in order to combat misunderstanding, both inside and outside the heritage professions.

For this mission, it is necessary to unite the people in the sector, to collaborate with other heritage professions and sectors, and with the culture landscape in general, for the common cause of conservation. Heritage conservation must have a central place in the Catalan cultural policy, and it must be provided with the necessary economic and human resources to be able to develop effectively.

Finally, the CRAC would like to thank the professionalism of Margarida Loran and the involvement of all the professionals and entities that have participated in the study, whether in the data collection (questionnaires), in interviews and discussion groups, in providing information or disseminating the questionnaires within their networks.

Notes

Center for the Restoration of Movable Property of Catalonia (CRBMC), Office of Cultural Heritage of the Barcelona Provincial Council (OPC), Culture Institute of Barcelona (ICUB), Museums and Archives Service of the Government of Catalonia, and the CRAC board.

Center for the Restoration of Movable Property of Catalonia (CRBMC), Office of Cultural Heritage of the Barcelona Provincial Council (OPC), Culture Institute of Barcelona (ICUB), Museums and Archives Service of the Government of Catalonia, and the CRAC board.

This definition has been developed in accordance with the professional guidelines of the European Confederation of Conservator-Restorers Organizations (ECCO). Document approved by its General Assembly. Brussels, 1 March 2002. ECCO. Professional Guidelines I: The Profession.

This definition has been developed in accordance with the professional guidelines of the European Confederation of Conservator-Restorers Organizations (ECCO). Document approved by its General Assembly. Brussels, 1 March 2002. ECCO. Professional Guidelines I: The Profession.

Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona, Graduate School of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage of Catalonia (ESCRBCC), CRAC, Nordest SL (a museology and museography company), ECRA SL (a conservation-restoration company), independent professional, National Art Museum of Catalonia (MNAC), Center for the Restoration of Movable Property (CRBMC).

Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona, Graduate School of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage of Catalonia (ESCRBCC), CRAC, Nordest SL (a museology and museography company), ECRA SL (a conservation-restoration company), independent professional, National Art Museum of Catalonia (MNAC), Center for the Restoration of Movable Property (CRBMC).

CRBMC, SAMs, Laboratory of the Cultural Heritage Office of the Barcelona Provincial Council.

CRBMC, SAMs, Laboratory of the Cultural Heritage Office of the Barcelona Provincial Council.

See this summary on page 84 of the preliminary study (2018).

See this summary on page 84 of the preliminary study (2018).

As a reference, the CRAC had 245 members at the time.

As a reference, the CRAC had 245 members at the time.

Response percentage: registered museums (50.5%), county archives (49%), municipal archives (18%), ecclesiastical archives (34.5%).

Response percentage: registered museums (50.5%), county archives (49%), municipal archives (18%), ecclesiastical archives (34.5%).

According to a survey by the Catalan University Quality Assurance Agency (AQU), the most common type of contract among C-R workers is that of self-employment (47%). Compared to other artistic postgrad degrees in Catalonia, this is the highest rate of all by far, and in some cases it even doubles others (in music, self-employment rates at 13.6%, and in theater at 23.4%). Source: 2017 AQU survey on job placement for 2012/13 and 2013/14 graduates. See page 15 of the study (2019).

According to a survey by the Catalan University Quality Assurance Agency (AQU), the most common type of contract among C-R workers is that of self-employment (47%). Compared to other artistic postgrad degrees in Catalonia, this is the highest rate of all by far, and in some cases it even doubles others (in music, self-employment rates at 13.6%, and in theater at 23.4%). Source: 2017 AQU survey on job placement for 2012/13 and 2013/14 graduates. See page 15 of the study (2019).

Considering the total number of respondents: 27% other non-working situation (full-time students, fellows, unemployed, retirement, others), 34% self-employed / freelancers, 17% working in a company, 16% working in a heritage center, 12% working in a public service specialized.

Considering the total number of respondents: 27% other non-working situation (full-time students, fellows, unemployed, retirement, others), 34% self-employed / freelancers, 17% working in a company, 16% working in a heritage center, 12% working in a public service specialized.

Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona and ESCRBCC.

Fine Arts Department of the University of Barcelona and ESCRBCC.

Project Management at the UB and C-R of Photographic Heritage at the ESCRBCC.

Project Management at the UB and C-R of Photographic Heritage at the ESCRBCC.

A significant number of professionals say they have a deficit of knowledge and skills, and most say they would enjoy training because they need it, especially in the field of contemporary art and modern materials. See page 34 to 40 of the study (2019) to learn about the needs for training or for external acquisition of very specific knowledge and skills, both for conservation-restoration interventions as well as preventive conservation and transversal competencies.

A significant number of professionals say they have a deficit of knowledge and skills, and most say they would enjoy training because they need it, especially in the field of contemporary art and modern materials. See page 34 to 40 of the study (2019) to learn about the needs for training or for external acquisition of very specific knowledge and skills, both for conservation-restoration interventions as well as preventive conservation and transversal competencies.

Specialized museums, archives and services, and national institutions.

Specialized museums, archives and services, and national institutions.

Management in reference centers, heads or technicians of C-R departments, management of companies, freelancers, professionals hired by companies that provide outsourced services, academic managers.

Management in reference centers, heads or technicians of C-R departments, management of companies, freelancers, professionals hired by companies that provide outsourced services, academic managers.

The 2018 CoNCA (National Council of Culture and the Arts) report recommends moving artistic studies to the university level. National Council of Culture and the Arts (2018). L’educació superior en l’àmbit artístic a Catalunya. Estudi i proposta d’organització. Informes CoNCA (IC15). The development project of the Arts Campus at Can Ricart (UB coordination) must be taken into account.

The 2018 CoNCA (National Council of Culture and the Arts) report recommends moving artistic studies to the university level. National Council of Culture and the Arts (2018). L’educació superior en l’àmbit artístic a Catalunya. Estudi i proposta d’organització. Informes CoNCA (IC15). The development project of the Arts Campus at Can Ricart (UB coordination) must be taken into account.

CRBMC, Barcelona City Council, territorial services and CRAC.

CRBMC, Barcelona City Council, territorial services and CRAC.

The professional sector (Technical Group, the ARCC and since 2013 the CRAC) has presented thirteen proposals to the Government of Catalonia in the last ten years, in addition to collaborating with the Association of Conservators and Restorers in Spain (ACRE) in another five statewide proposals.

The professional sector (Technical Group, the ARCC and since 2013 the CRAC) has presented thirteen proposals to the Government of Catalonia in the last ten years, in addition to collaborating with the Association of Conservators and Restorers in Spain (ACRE) in another five statewide proposals.

Margarida Loran, author of the study, has revised this article.

Margarida Loran, author of the study, has revised this article.

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY