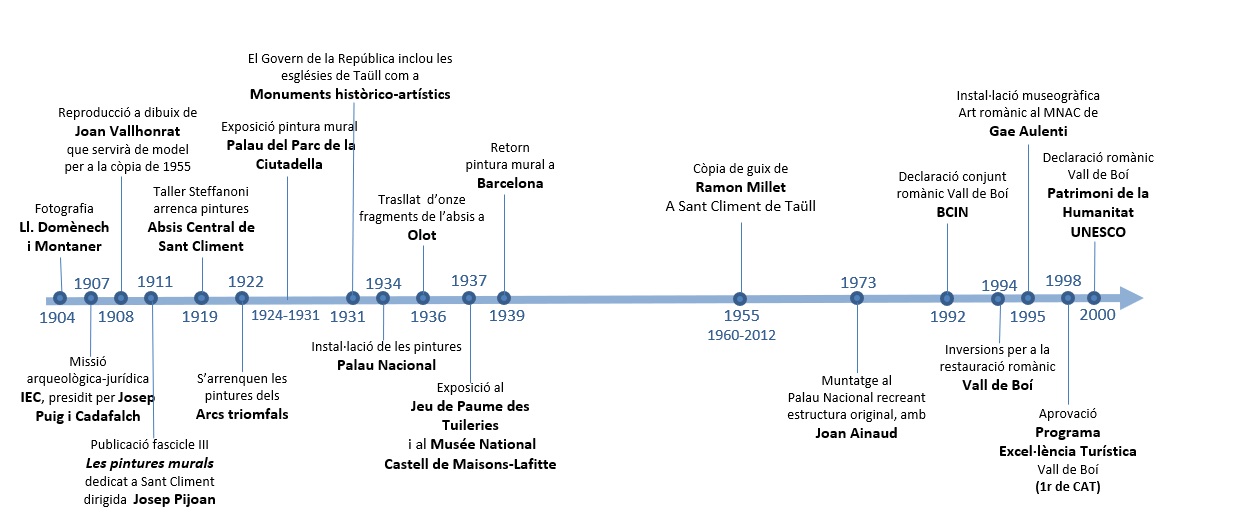

The year 2020 marks the centenary of the removal of the mural of Sant Climent de Taüll carried out by the Steffanoni workshop(1), commissioned by the Museums Board, to avoid its sale through its transfer to Barcelona. Almost ten years had passed since the publication in installments of Les pintures murals catalanes (The Murals in Catalonia), directed by Josep Pijoan, a seminal work that put Catalan Romanesque art into the European context. It was also just over a decade since the judicial and archaeological mission led by the Institute of Catalan Studies in 1908 under Josep Puig i Cadafalch’s direction.

The mural of Sant Climent suffered many vicissitudes during the twentieth century, with multiple transfers and museological adjustments—from Taüll to Barcelona, from the Palace of the Ciutadella to the National Palace, and then the trip to Olot and Paris before returning to Barcelona. However, this article focuses on the interventions in Sant Climent de Taüll and the Vall de Boí in the twenty-first century, especially on the replacement of a plaster replica of the mural by the central apse for a light and sound projection (mapping), a decision that has had an impact on improving the visitor’s experience, which has also impacted significantly on the number of visits and the generation of resources. It also improved the financial management of the Consortium and added to the museography, as this text tries to argue.

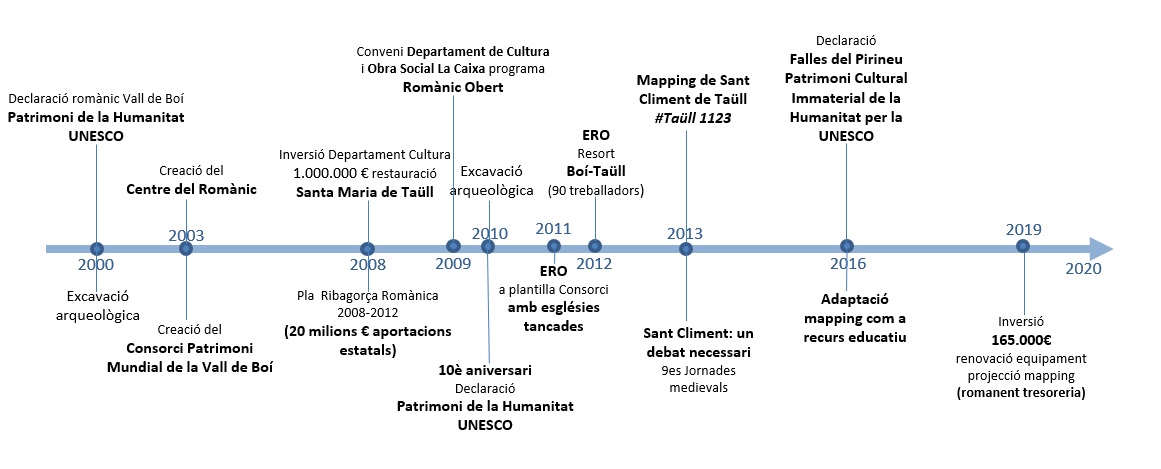

The management of Romanesque art in the comarca of Alta Ribagorça in the twenty-first century starts with a crucial accomplishment: the declaration of all churches of Vall de Boí as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO on 30 November 2000. The thrust of this declaration accelerated the creation of the Romanesque Centre and a consortium for the management of the Romanesque in the valley, and allowed public officials to formulate ambitious goals for the future of the monumental site. Shortly after the tenth anniversary of the UNESCO declaration, however, in a context of international financial crisis, a collective dismissal (called ERO in Catalonia) applied to the staff of the Consortium forced a significant reduction of the number of churches open to visitors as well as their opening times in one of the most known Catalan BCINs (from its Catalan designation, literally “Cultural Goods of National Interest”). The crisis of the Consortium overlapped with a massive ERO at the ski resort of Boí-Taüll too, precisely when the copy of the mural paintings of the apse needed some restoration after being exposed for fifty years. It was then that the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage, after a research process on the pictorial ensemble of Sant Climent, took the decision to replace a material museography for a virtual one using a mapping.

This article presents the background, the context and the process of creating this mapping, and the actors who intervened, and also analyzes its impact from the scope of the evolution of visitors, among other factors. It also reflects on mapping as a museographic strategy, and proposes some challenges for the management of the Consortium. In addition to secondary sources, investment data have been collected from the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage in Vall de Boí, and various professionals involved in the project have been interviewed. The author wants to explicitly thank Elena Belart, Sònia Bruguera, Cristina Castellà, Eloy Maduell and Albert Sierra for their contributions.

Sant Climent de Taüll, an Emblem of CataloniaRomanesque art in Catalonia has played an important role in building a collective imaginary and a sense of belonging, in a historiographical reading that starts in the Renaissance and finds its fulfillment in the Noucentisme. The hegemonic ideology of Catalonia in the early twentieth century greatly influenced a certain conception of cultural heritage, its social function, and the vision of the rural Catalonia as a deposit of essences and values which could substantiate the modern Catalonia that was being built. In this historical context Josep Puig i Cadafalch had a decisive influence. As stated by Riu-Barrera (2013), “he appreciated the exceptionality of the basilicas in Vall de Boí from an evolutionist and late positivist perspective. His vision and interpretation still stand today.”

The appreciation and interventions on the Romanesque in Vall de Boí during the first third of the twentieth century had a major influence, and nurtured other projects for the next forty years, such as the 1908 reproduction of Joan Vallhonrat, which served as a model for Ramon Millet’s 1955 plaster model and was exhibited in Sant Climent for half a century. In short, the Christ in Majesty presiding over the mural of the central apse of Sant Climent de Taüll has become, as claimed by Íbar, Riu-Barrera, Tarrida (2014), “the symbol of Catalan medieval art and the main piece of all Romanesque painting.” In the words of Guardia (2013), this Christ in Majesty embodies a certain “poetic vision of Catalonia,” and is a letter of presentation of Catalonia to the world, an image that always stands out in catalogs, brochures and promotional material of cultural tourism.

With the return of democracy, it was a priority for the cultural policy of the Catalan Government to crate large cultural infrastructures in Barcelona and its metropolitan area. This led to the creation of the National Museum of Science and Technology of Catalonia, the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, the renovation of the National Art Museum of Catalonia, the National Archive of Catalonia and the National Theater of Catalonia, as explained in the objectives of the Ministry of Culture Reports and its analysis (Font, Martínez, 2009, p. 43). Projects to update and digitalize heritage inventories as well as restoration programs were enhanced, but it is quite significant that in the presentation session of the conference “Sant Climent de Taüll, a necessary debate,” held at the MNAC in 2013, IRCVM (2013), the following was stated: “It was a hundred years ago that Taüll was discovered, and the monument had never allowed a meeting like this.” Although in the late twentieth century some substantial investments for the consolidation and restoration of the architectural ensemble were undertaken, its symbolic dimension was not well aligned neither with the management nor the communicative capacities. In fact, the Romanesque of Vall de Boí as a whole(2), was listed as BCIN only eight years prior to its declaration as a World Heritage Site.

A Grand Entrance in the Twenty-first CenturyOn 30 November 2000 the UNESCO distinguished the Romanesque churches ensemble of Vall de Boí as World Heritage. The dossier of the candidacy was promoted by the Lleida Provincial Council, the Ministry of Culture and the Vall de Boí City Council, and was prepared by Maria Carme Polo.

The declaration file(3) of the UNESCO emphasizes the joint value of the nine churches, their consistency and their exceptional state of preservation. It describes Vall de Boí as “the most important concentration of Romanesque rural churches in Europe.” The UNESCO also states that these churches and towns are the expression of medieval lifestyles of great importance in the recognition of Catalan cultural identity, and also that the Romanesque art of these Pyrenean locations had a vital role in the movement to restore the Catalan identity and nationality in the early twentieth century.

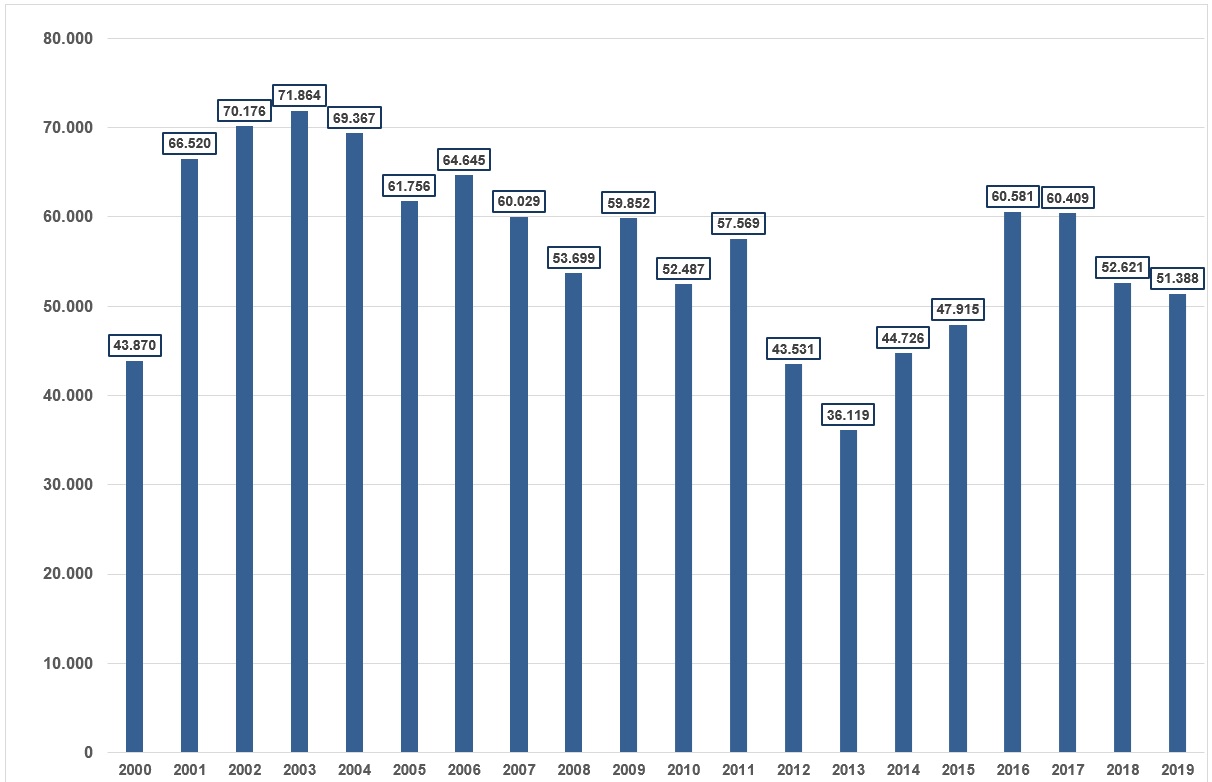

On the occasion of the UNESCO declaration, the images of Sant Climent appeared on the front pages of newspapers and opened television news in early December. The impact was immediate: the 43,870 received visits in 2000 increased by 50% in 2001, and reached the number of 70,176 in 2002.

The Consortium and the Romanesque Centre, a New Juridical Person and a New FacilityOne of the commitments of the bid submitted to the UNESCO was the creation of a visitor center and a consortium for the management of the monuments ensemble. With the push of the proclamation, the Vall de Boí World Heritage Consortium and the Romanesque Center of Vall de Boí were created in 2003.

The consortium is composed of the Government of Catalonia, the Lleida Provincial Council, the Regional Council of Alta Ribagorça and Vall de Boí City Council, each of them listed as a consortial person with ordinary contributions, and the Diocese of Urgell and the Diocese of Lleida as other consortial institutions, as specified in the statutes(4) of the Consortium.

The purpose and object of the Consortium include, in addition to the integral management of the churches, “the promotion, restoration, improvement and conservation of the cultural heritage of Vall de Boí,” and the “divulgation of traditional ways and lifestyles” and “actions to protect the natural environment and landscape” (articles 1 and 4 of the Statutes).

The Government Commission is the executive body of the Consortium, in which the Catalan Government has six representatives, the Lleida Provincial Council has four and the City Council, the Regional Council and both Dioceses have one each. The approval of the budget requires two-thirds of all votes in favor. The prevailing statutes, adopted on 2 December 2016, specify in relation to funding that “To the extent not covered by own revenues . . . the institutions assume the necessary contributions to meet the ordinary operation of the Consortium in the following distribution: 60% Catalan Government, 25% Lleida Provincial Council, 10% Vall de Boí City Council, and 5% Regional Council of Alta Ribagorça” (Article 13, paragraph 2 of the Statutes). The previous statutes, approved in 2014, did not foresee a scenario in which the necessary contributions could not be covered by the Consortium’s own income, nor specified any minimum contributions by any of the consortial administrations. This was a vague section in comparison to other consortiums.

Another important aspect is the figure of the Direction, which unfolds in Article 10 of the Statutes. The person who assumes the Direction is the “person responsible for the management and administration of the Consortium,” and the organic and functional management of the Consortium’s staff and its ordinary economic management stand among their duties.

The Romanesque Centre of Vall de Boí, located in Erill la Vall, is a facility that acts as a gateway to the Romanesque of the valley. A permanent exhibition provides the key information to understanding the churches as a whole. It describes the medieval society in the Pyrenees, gives details about the techniques for the construction of the churches, introduces the iconography and its interpretation, and also shows how did these churches look in the early twentieth century. The space offers information services, personalized and group visits, a shop with specialized Romanesque and cultural heritage publications and gifts. As explained on the website, the Center offers a wide repertoire of visiting possibilities, with differentiated prices: individual visit to Sant Climent, individual visit to other churches, a combined ticket for three churches, and even another combined ticket for Vall de Boí and the MNAC. It also promotes activities together with the three main leisure actors in the region: the National Park, the Caldes de Boí Thermal Resort and the Boí Taüll Resort. The Romanesque Center also hosts the headquarters and the offices of the Consortium.

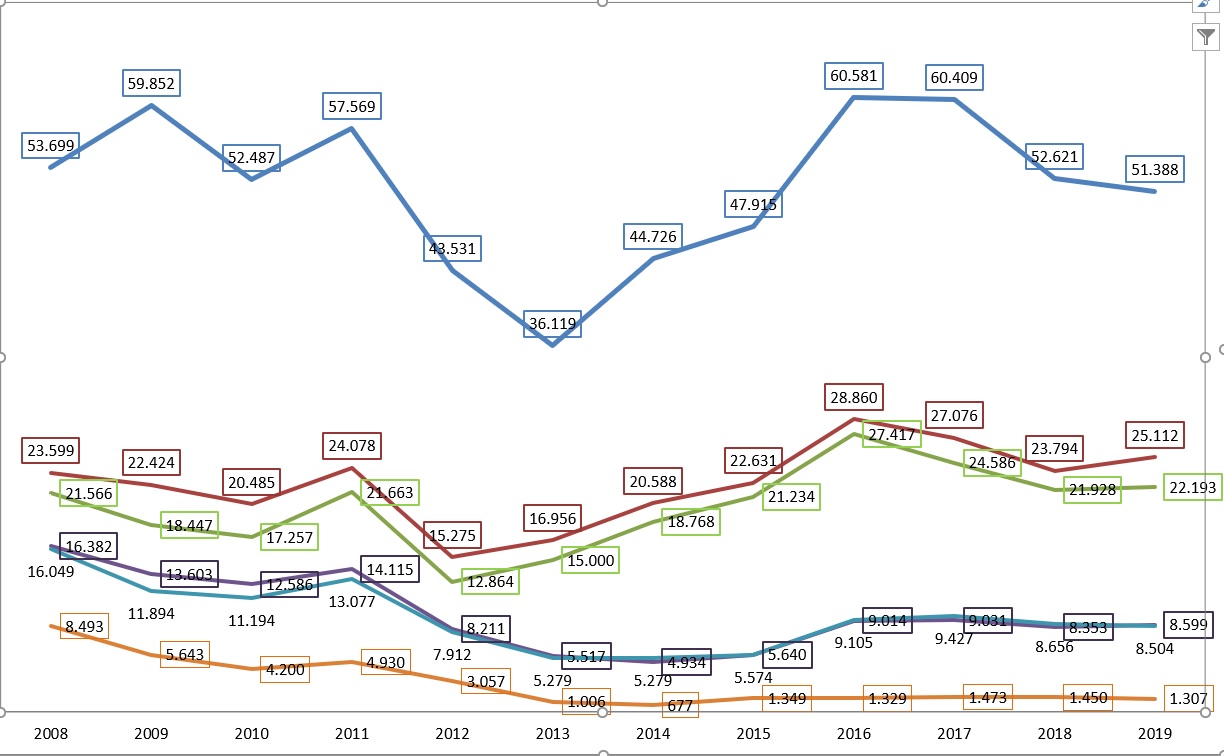

Years of Thrust and ConsolidationAs explained above, following the declaration of the UNESCO the number of visitors to the ensemble of churches in the valley changed threshold, and it did so in a sustained manner over time. The evolution of visits to Sant Climent de Taüll—the one with the longest sequence of homogenic data, since its entry is regulated with ticket(5) and it has been uninterruptedly open to the public—confirms this. In the 2001-2010 period, the average number of visits per year was more than 63,000. Given that in 2000 there were 43,870 visits to the valley, it can be said that the declaration helped to keep 40% more visitors for a decade.

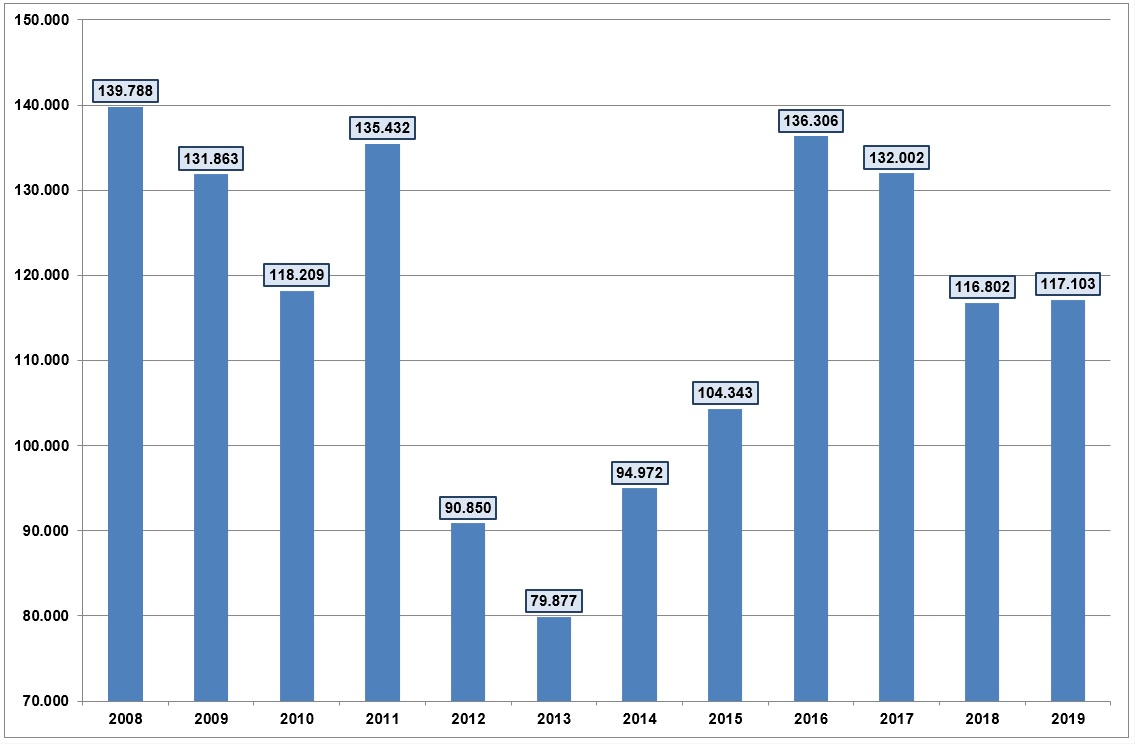

The evaluation by Joan Perelada—mayor of Vall de Boí for five legislatures—in 2007, on the occasion of the seventh anniversary of the declaration, serves as a testimony of that period (ACN, 2007). Perelada stressed that the Consortium managed an annual budget of circa 600,000 euros, that 3,000,000 euros were invested in the restoration of churches during those seven years, and that the year-round opening of the churches had been accomplished,(6), as well as the consolidation of a team of twelve people employed full-time as staff of the Consortium. The mayor said that the total number of visits, which that year was of 148,000, remained upward. He also announced new challenges, such as the lighting of some church and its accessibility, projects that were still pending in 2007.

In 2008 a study was carried out by Alcalde, Castellà, Rojas (2010) and directed by Gabriel Alcalde, from the Catalan Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (ICRPC), on the visitors to the valley. The research was commissioned by the Institute for the Development and Promotion of the Alt Pirineu i Aran (lDAPA), with the collaboration of the Network of Museums and Heritage Facilities of the Alt Pirineu i Aran, still active those years. The field work included surveys at the churches open to the public, at the Tourism Office of the valley and at the Romanesque Centre, which allowed the characterization of visitors(7), through the results on the origin, length of stay, accommodation, seasonality, composition and age of visitors, among others. The described tourist composition has not changed much ten years later, in comparison to the results from the National Park and the Tourism Office.

In that study, it stood out that 82% of the visits to Sant Climent were individuals, who recorded peaks of almost seven hundred visitors per day in summer or Easter. Among its strengths, the study highlighted the extended opening hours and days of the churches throughout the year, as well as the presence of specialized personnel for the reception, the opening of churches and the guided tours. In the section on conclusions Vall de Boí was characterized as a mature tourism destination linked to cultural and natural heritage. One thing that stuck out was the perception of the local population,(8), who felt very identified with the Romanesque Centre. Residents of the valley associated the Center with territorial development in the region, and even declared to mostly take part in activities organized by the Center because they felt involved. The monumental ensemble held attributes such as the World Heritage brand, which—along with the increasing momentum of inland rural tourism in 2008 and the identification of the residents of the valley with the project—allowed it to be classified as an “exceptional equipment” in terms of development.

As presented, since 2000, ten years of thrust, consolidation and international projection of the Romanesque in Vall de Boí followed, with the creation of the Consortium and the Romanesque Centre, as well as with a substantial increase of the number of visits and a technical team with a stable job. The good positioning of the destination was agreed upon, both regarding the academic contributions (ICRPC) and the statements of politicians, who announced ambitious goals for the Romanesque in the Valley.

The Program Open Romanesque, an Example of Public-Private PartnershipWhile the Consortium of Vall de Boí posed challenges of growth in infrastructure, financing and visiting public, in September 2007 the subprime mortgage crisis had just started in the US, and would eventually expand and transform into a global financial crisis. The crisis, however, did not bluntly shock the public sector in Catalonia until 2011, when it hit acutely and deeply, as it will be discussed later on.

In early 2009 the Ministry of Culture and L’Obra Social La Caixa signed an agreement to develop a program of conservation and promotion of Romanesque heritage in Catalonia. It was called Open Romanesque,(9) and aimed to protect, preserve and promote the Catalan cultural heritage. In October the agreement was ratified through the signing of specific agreements with the owners of heritage assets and real estate management entities, who were the recipients of subsidies. The six-year program had a budget of 15,146,000 euros.

The Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage was responsible for proposing and watching over the good execution of each project and action, and advised on them with their expertise in cultural heritage. It also monitored the interventions on monuments and acted as technical interlocutor to heritage owners and managers. Open Romanesque ultimately made it possible to carry out projects of the Directorate-General for which it did not have financial capacity anymore. It was a necessary condition—although not enough—for the mapping of Sant Climent de Taüll, the subject of this article. Seen in perspective, in the heritage sector, the agreement with L’Obra Social La Caixa allowed to anticipate and navigate a crisis that was imminent.

The Tenth Anniversary of the World Heritage Declaration, a Celebration Cut ShortThe year 2010 is a turning point in the trajectory of the Romanesque in Vall de Boí. On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the declaration of the UNESCO, a report called “Vall de Boí, a model of management and preservation” was written and brought to the UNESCO by Joan Perelada and Maria Carme Polo, author of the project, as an assessment. Perelada planned on duplicating the number of visitors in four years, hopping from 130,000 to 250,000, and announced the creation of an Ecomuseum in Durro, for which they had already acquired a building. A summary of the report pointed out the investment of more than 13 million euros in the “restoration of churches, remodeling of the surroundings and improvement of the Vall de Boí residents’ quality of life” from 2000 to 2010. It was a correlation of these investments in heritage, social and educational issues, such as the opening of a nursery, the construction of parking lots, the lighting of the churches, the improvement of the surroundings and the towns of the area, the recovering of traditional pathways, the consolidation of the Visitor Center and the construction of Casa del Parc in Boí.

In April 2010 the minister of Culture, Joan Manuel Tresserras, chaired the meeting of the Consortium’s committee. With the contributions to Open Romanesque, a budget of 1.4 million euros was approved, doubling that of 2009, which was 715,000 euros (ACN, CCMA, 2010). This is the highest budget ever approved. Among the planned interventions, there were the restoration of the church of Assumpció de Coll, the consolidation of the restoration of Santa Maria de Taüll and the work on original paintings discovered in the apse of the church of Sant Climent, an action that would eventually contribute indirectly to the creation of the mapping three years later.

In a few months, the situation turned upside down. The budget of the Ministry of Culture (Ministry of Culture, 2015) began to resent, and with little leeway in personnel costs and other structural items, consortial contributions stopped. The direct contribution of the Catalan Government,(10) which in 2010 was 192,000 euros, fell by 40% in 2011, and by 2012 there was a forecast of a new drop, which would reduce the transfer down to 92,000 euros. As there was no liquidity nor prospects to reverse the situation in the short term, the Consortium had no choice but to file an ERO in December 2011 that affected the entire workforce. In 2012, almost all staff switched from the status of permanent to discontinuous, a situation that would not be reversed until five years later, in 2017, when it all came back to how things were before the presentation of the ERO. Of all the churches, only Sant Climent and Santa Maria de Taüll carried on opening mornings and afternoons, and all other churches closed or suffered drastic restrictions on their schedules.

And the consequences of the crisis in Vall de Boí did not end there, as the ski slopes and the hotel resort Boí Taüll, which already presented an ERO in 2009 and had suffered financial problems for years, filed another ERO in April 2012 affecting 90 workers, a decision with great social impact, considering that the valley is home only to a thousand people.

In 2012, the Government Commission of the Consortium, chaired by minister Ferran Mascarell, announced (La Xarxa, 2012): “The Catalan Government seeks funding for the Vall de Boí.” The committee thought of the possibility that the students of Humanities and History of Art at the University of Lleida would undertake their placement in the valley, so that they could reopen some churches. The minister was asked about the possibility that UNESCO considered whether they should hold their rating of Boí as World Heritage, an option that Mascarell described as “an absolutely speculative and unfounded possibility,” and added that the strong investment in the restoration of the churches “is a decisive factor for UNESCO.”

In the end, over the period of two years, the public management of culture in Catalonia went from a context of expansion to finding ways to ensure the survival of cultural facilities. This situation, which was universal, was intensely suffered in Vall de Boí.

The Mapping of Sant Climent de Taüll, Genesis and FormalizationAs presented in the previous section, the mapping project emerged in a very unfavorable economic climate, although with respect to the Romanesque heritage, this was partially mitigated by the Open Romanesque program. And added to the external context, Sant Climent itself also accumulated factors that made taking decisions urgent, such as those listed below:

—The reproduction of the plaster mural in the central apse had deteriorated after being installed and exposed to the public for fifty years.

—The intervention on the remains of the original paintings, undertaken in 2010, forced to crop a portion of the reproduction in its bottom.

—The original Romanesque painting discovered and restored in 2000 was yet to be integrated into the pictorial assemblage.

—The excavation of 2010 had uncovered the remains of Romanesque chancel, which had not been consolidated nor was exhibited.

—The archaeological excavations forced to withdraw the altar stone, so it was impossible to perform the Catholic worship.

As a first decision the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage took down the plaster copy to study the remaining paint in the deep layers of the apse, and from there on a research plan was developed with the MNAC. And so, for the first time, a thorough joint investigation with the MNAC on the original paintings preserved in Sant Climent could be undertaken. In the deep layers of the apse significant traces of paint were found—an unexpected finding—and could be restored later on. The discovery and identification of traces of Romanesque painting from previous phases was also significant, such as geometric ornamentation on the three lower windows of the apse and the white line decoration between the ashlars, from the very moment of construction of the temple, between the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The museographic challenge of integrating and displaying the new findings and the reproduction of the mural by the MNAC at same time in Sant Climent opened the door to considering the feasibility of a virtual museography. One of the people responsible(11) for the decision, Josep Manuel Rueda (personal communication, September 2018), stated that they did not hesitate at all once they saw the possibilities of the mapping. In the 2020 Barcelona, where there are even attractions of immersive experience like Ideal Digital Arts Center, which has had absolute success with both the public(12) and critics (Jordi Sellas, personal communication, January 2020), this option is a normalized alternative to the standard repertoire of museographic strategies. In 2013, however, it was a risky decision(13), applied to one of the most emblematic monuments of Catalonia, a church that the population of the valley perceived very much as their own (Cristina Castellà, personal communication, December 2019).

As it was included in the program Open Romanesque, L’Obra Social La Caixa funded the project in coordination with the technical team of the Directorate-General for Heritage and the MNAC. Specialists of a broad range of profiles participated: archaeologists, architects, technical architects, curators, draftsmen, historians, museographers, restorers. Two Catalan firms integrated in the work team provided with the technological development: Burzon Comenge undertook the audiovisual project and the animation, and Playmodes was in charge of technical development and musical composition.

The process of creating the mapping required a virtual model of the temple made with a 3D laser scanner to obtain its geometry and its texture after the restoration. In parallel, a photographic process of the original painting of the MNAC was conducted, and then added to the model to obtain a complete virtual reconstruction. Thereafter the mapping process began. The images from the video projectors fitted precisely into the architectural space, which allowed lighting, painting and animating the space with a moving image.

It was decided not to make any public communication of the mapping until real testing on the walls of Sant Climent was cleared, because it was not possible to anticipate the reception that the recreated paintings and the 3D scanning would encounter.

In April 2013 the days “Sant Climent de Taüll, a necessary debate” took place. This meeting allowed experts to share and update all research and knowledge about Sant Climent as it had never been done before, integrating different specialties. It was possible to show all the restorations made on the mural, and the challenges ahead too. Or to discover the uniqueness of an architectural ensemble that reached the twentieth century virtually untouched, noting that the painting of the apse was never hidden, and was rather “protected” by a Gothic altarpiece. The attendees followed the different presentations that the mural painting had had over time at the Palace of the Ciutadella, the National Palace and Paris. During the event it was also stated that the yet so extended term “Pantocrator” should be replaced by the “Christ in Majesty.”

During those sessions the first public presentation of the mapping project was conducted, and it was announced that the equipment would be inaugurated in the upcoming fall. Albert Sierra, the Directorate-General for Heritage stated: “We will not make flying angels.” Years later, in another event, a brief observation from Sierra (2019) on the mapping helped characterizing it: “It is not a show,” he said.

The mapping, called “#Taull 1123”, was presented to the public in November 2013. As it is well known, it is the virtual recreation of the mural of Sant Climent, with a museography that helps visitors understand what the painting technique of Romanesque frescoes was, showing hierarchically the various iconographic representations that make up this mural painting. The presentation of paintings runs through three stages:

—The deep original paintings preserved in situ.

—The mural kept in the MNAC, together with fragments existing in Sant Climent.

—The reconstruction of the paintings in the church, with the restitution of the lost fragments.

The realization of the mapping is based on historical accuracy. The analysis of colors by the MNAC and the reconstruction of the remains on the walls, motifs and patterns, which are geometric and serial, allow to reconstruct the presbytery with scientific criteria, with the maximum accuracy to the original color.

The screening is done with six high definition video projectors that fill the entire central area of the church with images. The devices are integrated in a way that they do not alter the intrinsic nature of the Romanesque building. With the restoration of the pavement and the base of the old altar, uncovered by archaeological excavations, both cultural and liturgical uses of the apse are compatible.

The mapping goes on for ten minutes with no voice narration. It had a cost of 390,000 euros, financed exclusively by L’Obra Social La Caixa. This budget does not include the contributions of staff by the Directorate-General and the MNAC. Both assumed a highly specialized workload of many months that would result in a considerable amount of money, and which is a strategic contribution due to its expertise.

The mapping, in short, is the result of a thorough research work; an example of a successful public-private partnership, made up of a multidisciplinary team of specialists. It is a testimony that in Catalonia there is an ecosystem of creative professionals with an important degree of technological development(14), comparable to that of the most advanced countries. This is an empirically supported statement (Catalan Institute for Cultural Companies, 2019).

The mapping of Sant Climent de Taüll was inaugurated in late November 2013. Its launch, however, was not associated with any communication campaign; news about the presentation and word of mouth were the only channels to reach the public.

With the certainty that a new, high quality service was being offered to visitors, on the prior days before the inauguration it was decided to modify the price of the visit, which went from 2 euros to 5 for an individual entry. Given the economic fragility of the Consortium at the time, any tariff modification entailed both opportunities and risks. With numbers in hand and with 36,119 visits in 2013, this change in the price could mean going from 72,238 to 180,595 euros in own revenue, a difference that could allow the Consortium to hire the required staff for the opening and tour visiting of the other churches again. The reaction of the demand side to the new price would be based on the perceived quality of the experience of the mapping, a response that did not take long to arrive.

In 2014 visits to Sant Climent increased by 20%, and by 2016 the growth was already more than 50% compared to 2013. The ability of #Taull 1123 to attract the public led to an increase in visits to other churches in the valley, and made it possible to recover the full staff that had previously worked in the Consortium.

The data of all payment churches—it has been mentioned that the visit to Santa Maria de Taüll is free of charge—shows the evolution of visits. Parting from a bottom point in 2013 of 72,238 visits at the time of maximum recession, they rose up to 136,306 visits in 2016, a 70% increase. The impact of the mapping on the audiences of the Romanesque is comparable or even superior to that of the declaration of World Heritage by UNESCO back in 2000. The mapping of Taüll acted as an economical catalyst in a region in crisis. However, to get a broader perspective, it should also be said that in late 2014 the Catalan Government acquired the credit of 7.3 million euros that conditioned the future of the Boí-Taüll ski station, in addition to a direct contribution of 1 million euros to ensure the continuity of the resort. All this made it possible to reverse the situation.

Quantitative data aside, the book signings at Sant Climent and especially the comments on TripAdvisor also provide information on the perception of the mapping. Out of the 414 people who had classified their experience on TripAdvisor by mid-2019, 80.6% rated it as excellent, 16.1% as very good, 1.9% as regular, 0.9% as bad and one person described it as terrible. Generally, comments written in English are more favorable than those written in Spanish, where there are complaints about the ticket price considering that it is a church or because in some cases it is not perceived that the mapping adds any value. The following four comments have been selected as an example:

“El video no tiene sentido […] es un visual que no tiene más audio que un sonido de tiza en la pizarra”. (The video doesn’t have any sense . . . it is a visual that doesn’t have more audio than the sound of a piece of chalk on a board.)

“Muy bien conservada y parece ser que la visita es espectacular, pero me parecen demasiado 5 euros cuando la restauración fue pagada por Endesa”. (Very well preserved, and it seems like the visit is spectacular, but I think that 5 euros is too expensive considering that Endesa [Spanish electric utility company] paid for the restoration.)

“Magical and moving. A wonderful example of the architecture and construction of these ancient churches, but the son et lumière show was out of this world—stunning, impactful, informative and moving.”

“We were so surprised when we were seated in the dark and this fantastic digital illustration of the frescos appeared instead, accompanied by beautiful music that made it a rather emotional experience.”

There are positive reports too from members of the clergy who value (Aran, 2016) the evocative capacity of the mapping: “The video mapping offers the possibility to merge the experience of going to the movies with the silence of spirituality, which is unthinkable in a conventional visit.”

The recognition to the mapping went beyond the response of the public, because in 2014 it was awarded by the prize Museums and the Web, a US platform which is a world leader in innovation and creativity in museums and heritage.

#Taull 1123 won the Best Rich Multimedia Project Award,(15) whose previous recipient was the Museum of Contemporary Art of Australia in 2013. That 2014, among all awarded museums, there were the MoMA in New York, the Dallas Museum of Art or the Imperial War Museums in Britain. #Taull 1123 was the only awarded project from continental Europe.

The international dimension of the award-winning museums, with the volume of financial and human resources they manage, contrasts and lifts the distinction of #Taull 1123 even higher—a project created, developed and produced by professionals from the public sector and from small private studios in Catalonia. In addition to this award, the Association of Art Directors and Graphic Designers of Catalonia also granted one of the Laus Awards to the mapping of Sant Climent.

What are the keys to the success of the mapping in Taüll? The artistic, historical, scenic and symbolic context of the monument, and its international recognition are important factors, just like the research carried out on the building and mural painting. However, these external variables are not enough. The piece #Taull 1123 has creative and prototypal components that, like in film production, do not allow to anticipate any possible outcomes from the planning of the elements that form it (duration, sound, light, script, images). It is also a relatively new language in its application to heritage. The decision to discard verbal narration, the musical composition, the absence of effects, the rhythm and the will not to make a show out of it succeed in making visitors able to experience the live restitution of the original paint from the twelfth century, now even better illuminated, while still honoring the value of the existing paint in situ. This result, the ability to convey those feelings, requires a balance of factors that is very difficult to standardize, and it has been achieved, as unanimously claimed by interviewed agents who participated int the process and users.

It is likely that mappings with effects at major events and commemorations, projected in large format on emblematic facades, have a close obsolescence once the viewer has seen a few. In contrast, mappings as a museographic element could be right at the start of their journey. Take, as an example, the mapping of the mosaic in the circus of the Catalan Museum of Archaeology, inaugurated in late 2019. For the required resources, it is a project available to most museums, and brings the original mosaic back to life, as well as making the piece more attractive to the young segment of the population who feel the audiovisual language as natural. The mapped layer complements, enhances and adds value to the original piece, making it more understandable.

In contrast, in mid-2019 the multimedia installation “In the Shadow of the Moor” debuted at Sala delle Asse, in the Castello Sforzesco in Milan, to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci. After a six-year process of restoration(16), a mapping restituted a mural from 1498, highlighting a little-known piece by Leonardo, badly damaged by later interventions, in one of the main monuments and art museums in Lombardy. In this case, the itinerary of the visit to the museum, the capacity of the room and the cadence of the mapping caused, first of all, a slowdown in the rooms, and queues in previous halls of the castle. While sitting in the Sala delle Asse, the mapping recreates the painting of a trellis of mulberry trees. Starting from the roots, it goes up the walls and ceiling of the room, showing its branches and leaves, and covering the walls and ceiling of the hall. The restitution of this mural, considering the investment made in restoration and production, and because it is a work of Leonardo da Vinci and given the size of the room, could make this mapping exceptional. However, yours truly believes that the experience is undermined by the dramatized narration included in the restitution of the painting, which is projected on the floor of the room where the moment of the commission to Leonardo and his stay at the castle and the city of Milan are staged, with the interaction of the characters. This distracts attention from the restoration of the paintings, and mitigates their prominence, making the museographic strategy confusing (Contin, Paolini, Salerno, 2014).

The case #Taull 1123 is also a contribution to the museography regarding the use of replicas. The mapping, as mentioned above, enhances the paintings preserved in situ, reproduces the murals preserved in the MNAC and restores the original paint. Given the symbolic dimension of Sant Climent, it could stand—in spite of the enormous distance in time, materials and concept—by the replica of the bison on the ceiling of the cave of Altamira, which was a milestone in the field of museography back in 1959 that brought Prehistory close to the public. At the time, it was the Deutsches Museum of Munich that brought the technology on the table, while in Sant Climent it was all developed with local technological resources. The use of replicas allows the preservation of the original—in this case at the MNAC—while providing better conditions for reading, experiencing and understanding the work than the original. The mapping enriches the debate on the triangle of the sustainability of heritage and its assessment, as posed by Miró (2020) when speaking about the tension between the original and the copy, and in relation to the quality of the experience of the representation.

In late 2018, an agreement with the Government authorized the World Heritage Consortium Vall de Boí to allocate 165,000 euros for the replacement of equipment in the mapping of Sant Climent. This investment was on account of the remaining cash that the institution had managed to save when closing the accounts for the year 2017. Six years after, replacing the first projectors for more efficient ones has led to further increase the quality of the visit. The mapping in early 2020 swaddles the visitor as ever. The renewal of projectors with the remaining funds of the very institution is an indicator of its ability to generate own resources. The economic structure of the Consortium is presented below.

In 2017, own resources (tickets, guides and interpreters’ services, and store sales) accounted for 85.6% of the total budget, a percentage that was 70.3% and 72.2% in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

All staff expenses, including the contributions to the Social Security, accounted for 68.8% of the expenditure budget in 2018. They are fully covered by revenue from the box office. For the maintenance of the churches, the General-Directorate for Cultural Heritage transfers each year an amount that in the period 2010-2017 averaged 65,207 euros per year. The Consortium of Boí, therefore, has a very high self-financing capacity, when contextualized in the whole visited architectural heritage in Catalonia. Operating expenses are fully covered by the contributions of visitors, investment and maintenance aside.

From 2016 to 2019, Sant Climent lost 15% of visitors, a higher percentage than other churches in Vall de Boí. This—moderate—decrease is higher than that of the visits to the National Park (Government of Catalonia, 2019), which is 5.8% over the same period. In the case of visitors attended at the Tourist Office of Barruera the same decline has been even lower. Therefore this 15% responds to specific own factors. Regardless of other variables of tourism composition in the valley,(17), most visitors come from Catalonia, in a percentage that in the last ten years has fluctuated between 60% and 65%. Cristina Castellà, from the Consortium, stated: “Many visitors repeat. The mapping has people coming in from Val d’Aran, from Pallars, from second homes—these also bring friends.” No matter how much they repeat, it is clear that the mapping has a ceiling for an audience that already knows it, if it cannot be complemented with other cultural experiences related to heritage.

As mentioned before, the structure of the Consortium comprises four public administrations and two dioceses. Although the Catalan Government has a majority, the plurality of actors can lead to a confusing governance when making certain decisions and taking risks, because it hinders clear leadership who is identified as responsible accountable.

It was also mentioned earlier that the Consortium’s Statutes regulate the Direction and its functions. Since its creation in 2003, the Consortium never adopted a Direction in a situation where for a few years, as it has been assessed, there has been substantial economic surpluses. Having a Direction could favor the formulation and the achievement of measurable objectives in various areas: planning activities, creating cultural tourism products, having a central for reservations, better divulgation, increasing the amount of agreements with economic actors of the territory, internationalizing the space, and so on. The Statutes state explicitly that among the functions of the Consortium there is the documentation and enhancement of traditional ways of life, and the management of the cultural heritage of the valley. These are neglected functions that with this provision could allow the Consortium to position itself as a dynamizing cultural actor of the valley across the whole spectrum of cultural management, beyond the Romanesque heritage itself, assuming functions that typically belong to museological facilities.

Addendum. “The Future’s not Ours to See”This article was finished a few days before the start of the confinement and the shutting of cultural facilities for the pandemic of the Covid-19. For its publication, it seemed appropriate to update its content so that it includes how the Consortium faced this new situation in early May, and to present some prospective variables and arguments, with all the required provisionality and caution when forecasting anything before such a dynamic reality.

With the renewed audiovisual equipment of the mapping, expectations for the beginning of this season were optimistic, because Easter is a period of great public attendance—although it does not reach the numbers registered in summer—and, therefore, of increased revenue. But once Easter was lost for good, the degree of openness of the churches in summer was unknown. By the first week of May the decision on the celebration of the Falles was on the table. Its organization in Vall de Boí depends to a certain degree on the residents of each town. After five years of the World Heritage Site declaration, the Falles do not pose major overcrowding problems, also because the calendar, instead of concentrating on the solstice, is distributed in many weeks of summer. The agenda for 2020 planned to start the cycle in Durro on 13 June, and then to keep going until 17 July around Boí, Barruera, Erill la Vall and Taüll, with a festive walk to Pla de l'Ermita on 14 August. Holding or cancelling the Falles has an impact on the summer season and on the attendance to churches.

In the short term, the drastic reduction in mobility and the break in cultural consumption outside home will affect the monumental ensemble acutely, just as elsewhere. However, there are specific forecasts that are very positive for the Vall de Boí. A survey conducted in late April by the Laboratory for Cultural Tourism and Heritage(18) of the University of Barcelona to five hundred tour operators shows that the favorite destinations—omitting international destinations—are concentrated around the Ebro Delta, the Costa Brava and the Pyrenees, with percentages of 30%, 28% and 20%, respectively. These can be the major chosen destinations during the summer of 2020. As for the activities to undertake, the professionals of the tourism sector are inclined to everything that can be done outdoors, like visiting towns or historical sites and traditional festivities. But there is still another factor that can help increase the choice of Vall de Boí as a destination, and that is the little impact that Covidien-19 has had in the region. Official records state that there has been only one positive case until 3 May (Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Evaluation, 2020). In this episode, there have been two deaths in the region of Alta Ribagorça, which contrasts to the seventeen deaths in the neighboring regions of Pallars Jussà or the six more in Val d'Aran and Alt Urgell. Only Pallars Sobirà remained with no deaths during this period.

In addition to the authorization to reopen the churches, there are several factors that will determine the visits to the mapping of Sant Climent and to the interior of the remaining churches. Sònia Bruguera, mayor of Boí and vice-president of the Consortium, believes that in order to ensure the security of visitors inside Sant Climent they might need to hire another person whose role is additional to ticketing, a requirement that is considered impracticable by now. In early May, there are still no protocols that are clear enough regarding the staff’s PPE nor the procedures and specifications of products for the disinfection of spaces in the case of heritage assets(19) (Cultural Heritage Institute of Spain, 2020).

In anticipation of a reopening in summer, the Consortium is organizing new guided tours for visitors, prioritizing outdoor spaces of the churches because they have more maneuverability for the requirements of social distancing. The option of opening the interior of the churches alternately is also under evaluation, so that a person who makes a three-day stay in the valley can visit them all.

The economic situation resulting from the pandemic is the last factor discussed in this addendum. Here, the procedures carried out by the Consortium of Vall de Boí are presented, and a comparison to the 2010 crisis, just a decade ago, is established. The economic structure of the Consortium can deal with the regular expenditure budget with its own revenue. Now, after remaining closed for two months—losing Easter in the process—, enduring an atypical summer, and seeing forecasts of a slow recovery, the treasury management is a critical factor to deal with the expenses exposed in chapter I. That is why, in late April, Sònia Bruguera had already asked the Ministry of Culture of the Catalan Government for their total contribution of the year, a transfer that is usually facilitated on a monthly basis. The first week of May, the Lleida Provincial Council had already paid the total contribution of 2019, and was processing 85% of the contribution envisaged for 2020. These arrangements will at least provide liquidity in the short term.

The Consortium, seeing the mandatory closure of its churches, thought about the idea of presenting an ERTO, a possibility not existing within the current legislation in consortia with a majoritarian participation of the public administration. Comparing the current applicable regulations to those existing back in 2010 is relevant because, in the case of Boí, the decrease in contributions from the Government forced to apply an ERO to the whole staff a decade ago. State law 27/2013 on rationalization and sustainability of the local administration, known as LRSAL, led to substantial changes in the rules of consortia and their staff, assigning them to the majoritarian administration.

With the prevailing Statutes, and in relation to the those from 2014, the viability of the Consortium is better guaranteed, because the previous statutes did not specify any obligation to the Government in case that own resources did not reach to face the expenditures. With the current Statutes, the different administrations will have to cover the loss of income from visitors with a prorate of 60% for the Ministry of Culture, 25% for the Lleida Provincial Council, 10% for the City Council and 5% for the Regional Council. The legal changes of the LRSAL were subject to much criticism by the local administration, as shown in Forcadell, Pifarré, Sabaté (2014). Nevertheless, they currently guarantee the stability of the Consortium because it is now fully equated to the public sector, unlike ten years ago.

Regarding the impact of the Covid-19 in culture, Bonet (2020) states that “the 2008 crisis caused a brutal reduction of available resources, resources that have not been recovered ten years later.” As noted in this article, the crisis from a decade ago was not foreseen. Bonet: “Cutbacks did not come from a thoughtful strategy, they only saved those activities that had less political or accounting costs, the most institutionalized projects, those with civil servants . . . The same management mistakes of the 2008 crisis should not be repeated, because the cultural sector is now weaker than it was at the time.”

Vall de Boí and Sant Climent de Taüll suffered a major crisis in 2011. The mapping analyzed in this article was a reaction and a response, made from creativity and teamwork, a decision that acted as territorial stimulus, a decision that nobody could have foreseen ten years ago. The future, which was not made to be foreseen, is also written with each of our initiatives and decisions.

Notes

Steffanoni, family name of a highly reputed family-run workshop in Bergamo. They were in Catalonia precisely to extract murals, and export them to the United States.

Steffanoni, family name of a highly reputed family-run workshop in Bergamo. They were in Catalonia precisely to extract murals, and export them to the United States.

Sant Climent and Santa Maria had been declared national monuments in 1931, during the Provisional Government of the Republic, and Sant Joan de Boí and Santa Eulàlia d’Erill la Vall in 1962.

Sant Climent and Santa Maria had been declared national monuments in 1931, during the Provisional Government of the Republic, and Sant Joan de Boí and Santa Eulàlia d’Erill la Vall in 1962.

Statutes of the Vall de Boí World Heritage Consortium. (2 December 2016).

Statutes of the Vall de Boí World Heritage Consortium. (2 December 2016).

The entrance to the church of Santa Maria de Taüll has always been free. For its physical proximity to Sant Climent, it is estimated that the number of visits to Santa Maria is equal or greater than to Sant Climent. The data regarding the numbers of visitors in this article refer only to visits to the payment churches, since it is not possible to keep track of visits to Santa Maria.

The entrance to the church of Santa Maria de Taüll has always been free. For its physical proximity to Sant Climent, it is estimated that the number of visits to Santa Maria is equal or greater than to Sant Climent. The data regarding the numbers of visitors in this article refer only to visits to the payment churches, since it is not possible to keep track of visits to Santa Maria.

The churches of the Vall de Boí opened daily from 10 to 14 and from 16 to 19, with an amount of annual opening hours on the fringe of the largest museums in Catalonia.

The churches of the Vall de Boí opened daily from 10 to 14 and from 16 to 19, with an amount of annual opening hours on the fringe of the largest museums in Catalonia.

Data on the origin, seasonality and composition of visitors and their evolution over time are comparable to the analysis made public every year in the National Park, as well as the composition of people who make consultations at the Tourism Office of Barruera.

Data on the origin, seasonality and composition of visitors and their evolution over time are comparable to the analysis made public every year in the National Park, as well as the composition of people who make consultations at the Tourism Office of Barruera.

As a result of the survey, 92% of the local population knew the Visitor Center and could place it, 80% had visited it, and, above all, 56% stated they had attended an activity organized by the Center.

As a result of the survey, 92% of the local population knew the Visitor Center and could place it, 80% had visited it, and, above all, 56% stated they had attended an activity organized by the Center.

The full name of the program was Open Romanesque and Co-operative Cellars. Regarding the Romanesque, an intervention in 75 monuments and 8 cellars was planned. The total budget, which was distributed in six annual installments, added up to 18,046,000 euros, out of which 84% was used in Open Romanesque.

The full name of the program was Open Romanesque and Co-operative Cellars. Regarding the Romanesque, an intervention in 75 monuments and 8 cellars was planned. The total budget, which was distributed in six annual installments, added up to 18,046,000 euros, out of which 84% was used in Open Romanesque.

It includes the contributions of the Ministry of Culture, which are recurring, and those from the Ministry of Agriculture, linked to European structural funds.

It includes the contributions of the Ministry of Culture, which are recurring, and those from the Ministry of Agriculture, linked to European structural funds.

Personal communication of Josep Manuel Rueda, who in 2013 was deputy director general of Architectural, Archeological and Paleontological Heritage. The decision on the mapping coincided in time with the organization of the Catalan Cultural Heritage Agency, which was created in 2011 with the Omnibus Act but was not activated until 2013 with the approval of the Statutes. Joan Pluma was the director general of Heritage and of the Agency.

Personal communication of Josep Manuel Rueda, who in 2013 was deputy director general of Architectural, Archeological and Paleontological Heritage. The decision on the mapping coincided in time with the organization of the Catalan Cultural Heritage Agency, which was created in 2011 with the Omnibus Act but was not activated until 2013 with the approval of the Statutes. Joan Pluma was the director general of Heritage and of the Agency.

Opened in late October 2019, with a price range between 9 and 16.5 euros for the individual ticket. Jordi Sellas, director, declared that by late December they had already reached 60,000 visitors. https://idealbarcelona.com

Opened in late October 2019, with a price range between 9 and 16.5 euros for the individual ticket. Jordi Sellas, director, declared that by late December they had already reached 60,000 visitors. https://idealbarcelona.com

Cristina Castellà, from the World Heritage Consortium Vall de Boí, declared: “It was difficult to convince some people here. I saw it very clearly, because I trusted the team behind it. Now everyone knows what a mapping is, but no one knew back then. We had to explain it very well to people—here the church is like home them. They feel it very much theirs. It is not like the Sagrada Família in Barcelona. Many perceived it as if we were about to intervene in their dining rooms back home.”

Cristina Castellà, from the World Heritage Consortium Vall de Boí, declared: “It was difficult to convince some people here. I saw it very clearly, because I trusted the team behind it. Now everyone knows what a mapping is, but no one knew back then. We had to explain it very well to people—here the church is like home them. They feel it very much theirs. It is not like the Sagrada Família in Barcelona. Many perceived it as if we were about to intervene in their dining rooms back home.”

The turnover of the companies related to augmented reality, immersive experiences and video games based in Catalonia has a annual growth rate exceeding 20%. In 2017 they had the 52% turnover countrywide, and they had a forecast to reach 5,400 direct workers by 2020. In Catalonia, this dynamic, innovative, close cluster brings an opportunity for the development of cultural heritage.

The turnover of the companies related to augmented reality, immersive experiences and video games based in Catalonia has a annual growth rate exceeding 20%. In 2017 they had the 52% turnover countrywide, and they had a forecast to reach 5,400 direct workers by 2020. In Catalonia, this dynamic, innovative, close cluster brings an opportunity for the development of cultural heritage.

Because of space limitations, further data on the origin, seasonality and composition of visitors to the National Park and the attendees at the Tourist Office of Barruera was omitted.

Because of space limitations, further data on the origin, seasonality and composition of visitors to the National Park and the attendees at the Tourist Office of Barruera was omitted.

IBERTUR. Laboratori de Turisme i Patrimoni Cultural de la Universitat de Barcelona. Enquesta feta a 500 agents turístics de Catalunya (agències de viatges, empreses de transport, allotjaments, guies, etc.) amb un índex de resposta del 85%.

IBERTUR. Laboratori de Turisme i Patrimoni Cultural de la Universitat de Barcelona. Enquesta feta a 500 agents turístics de Catalunya (agències de viatges, empreses de transport, allotjaments, guies, etc.) amb un índex de resposta del 85%.

En el moment de tancar aquesta addenda el Servei de Museus de la Direcció General del Patrimoni estava ultimant uns protocols per a la reobertura dels museus.

En el moment de tancar aquesta addenda el Servei de Museus de la Direcció General del Patrimoni estava ultimant uns protocols per a la reobertura dels museus.

Bibliography

ACN (2007, 1 December). La Vall de Boí celebra el VII aniversari de la declaració de les seves esglésies com a Patrimoni de la Humanitat. Racó català. Visited on 1 December 2017 at https://www.racocatala.cat/forums/fil/76650/vall-boi-celebra-vii-aniversari-declaracio-seves-esglesies-com-patrimoni-humanitat?pag=0

ACN, CCMA (2010, 9 April). S'aprova un pressupost de 1,4 milions d'euros pel Consorci Patrimoni de la Vall de Boí. CCMA. Visited on 9 April 2010 at https://www.ccma.cat/324/saprova-un-pressupost-de-1-4-milions-deuros-pel-consorci-patrimoni-de-la-vall-de-bo/noticia/613987/

Agència de Qualitat i Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya (2020), updated data on SARS-CoV-2, visited on 3 May 2020 at http://aquas.gencat.cat/ca/actualitat/ultimes-dades-coronavirus

Alcalde, G.; Castellà, C.; Rojas, A. (2010). “La visita patrimonial a las iglesias románicas de la Vall de Boí (Cataluña)”. A A. Muñoz (dir.), Patrimonio e innovación. Patrimonio Cultural de España, no. 4. Gobierno de España. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (p.178-191).

Aran, E. (2016) “Videomapatge patrimonial a Taüll”. Catalunya Religió. Visited at https://www.catalunyareligio.cat/ca/blog/betel-arquitectura-art-religio/videomapatge-patrimonial-taull-208884

Bonet, Ll. (May 2016). “Reflexions sobre l'impacte del COVID-19 en la cultura (5): per una nova agenda de política cultural”. Visited at https://lluisbonet.blogspot.com/?fbclid=IwAR2-yPnSAQUF0dfLxIrjSj5Pj5TB9X0vbC0s0hMpKseNhd6rEQzvokOxZ_0

Contin, A.; Paolini, P.; Salerno, R. (2014) [eds.] Innovative Technologies in Urban Mapping: Built Space and Mental Space. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-31903797-4

Departament de Cultura (2015). De Cultura. No. 18 April 2015. Visited at https://dadesculturals.gencat.cat/web/.content/dades_culturals/09_fulls_decultura/arxius/18-DeCultura_Pressupost_public_en_cultura_Catalunya.pdf

Font Sentias, J.; Martínez, S. (2009). “Infraestructures públiques al servei de la creació i de la comunitat”. A Ll. Bonet (coord.), L’avaluació externa de projectes culturals. Quaderns de Cultura, 3. (p. 43)

Forcadell, X.; Pifarré, M.; Sabaté, J. M. (2014). Els governs locals de Catalunya davant la reforma del règim local espanyol. Parlament de Catalunya.

Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Territori i Sostenibilitat (2019). Parc Nacional d’Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici. Memòria 2019.

Guardia, M. (10 April 2013). Sant Climent: la recerca versus la icona. [video] Visited at https://youtu.be/-x6WE4iX2qU IRCVM. Opening session at: 9es Jornades de Cultures Medievals “Sant Climent de Taüll, un debat necessari”.

Íbar, E.; Riu-Barrera, E; Tarrida, E. (December 2014). Sant Climent de Taull #1123: noves estratègies de restitució i divulgació del patrimoni a la Vall de Boí. Conference presented at: XXXVIIè Curset jornades internacionals sobre la intervenció en el patrimoni arquitectònic. “Patrimoni sacre: permanent innovació”. Barcelona: AADIPA; COAC. Summary recovered from https://upcommons.upc.edu/bitstream/handle/2099/16413/TaüllResumCurset.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Institut Català de les Empreses Culturals. Generalitat de Catalunya (2019). Llibre blanc de la indústria del videojoc 2018.

Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de España. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte (12, abril, 2020). “Recomendaciones sobre procedimientos de desinfección en bienes culturales con motivo de la crisis por COVID-19”. Visited at https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/cultura/Documents/2020/160420-RecomendacionesIPCE.pdf

IRCVM (2013). Sessió de presentació [video] 9enes Visited at https://youtu.be/-x6WE4iX2qU Jornades de Cultures Medievals “Sant Climent de Taüll, un debat necessari”.

La Xarxa (2012, gener 13). “La Generalitat busca finançament per a la Vall de Boí i redueix el seu pressupost”. La Xarxa. Visited on 13 January 2012. Visited at http://www.laxarxa.com/infolocal/lleida/noticia/la-generalitat-busca-financament-per-a-la-vall-de-boi-i-redueix-el-seu-pressupost

Miró, M. (2020). “Evolución de las réplicas de arte parietal, un equipamiento museístico singular”. E-rph. Revista electrónica de patrimonio histórico. No 25. p. 55-77. DOI: htpp://dx.doi.org/10.30827/erph.v25i5

Riu-Barrera, E. (10 April 2013). El projecte de nova configuració de l’absis major de Sant Climent de Taüll. [Video] Visited at https://youtu.be/YMtBTmqewu4. IRCVM. Conference presented at: 9enes Jornades de Cultures Medievals “Sant Climent de Taüll, un debat necessari”.

Sierra, A. (7 February 2019). Del 3D a les experiències immersives. [Video] Agència Catalana de Patrimoni Cultural Jornada Patrimoni & Digital. Museu Episcopal de Vic. Visited at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PyoA3OhaUw

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY