In June 2019 we attended the first Forum of Museums of Catalonia, organized by the Department of Culture of the Government of Catalonia (https://forumdelsmuseus.cat/). Its leitmotif, “Organizations as an engine of change for the social museum.” The Forum presented the main themes of discussion and improvement for the Catalan museums today, focused on their governance, their strategic management, work units and professional career. Each of these issues itself would represent a new forum, and many voices talked about each thematic area.

Two ideas probably consolidated there, and we will remember that day by them. The first one suddenly became the hashtag of the day, #conjurem-nos (meaning “team up”, by @RosichMireia), and the second was the work of Pepe Serra (director of MNAC) “Change requires radicality.” Both ideas take on their meaning concepts that are inherent in innovation.

What is innovation?In business and technical terms, innovating is not limited to having a plan for R & D and innovation. It means risk and understanding innovation as an ecosystem of organizations that goes beyond technology. It is a strategic approach that extends to all areas of an organization (or should at least). Innovating is changing things in a positive sense for companies and organizations, and especially for their customers and users. This innovation can be oriented to new products or services, new ways of organizing, new processing models or new technologies. But ultimately, any innovative change must aim to achieve an improvement that is perceived by both the user/consumer and the organization. Because the difference between change and innovation lies precisely in the acceptance by users of this positive change. We can change many things in our organizations, but if these changes are not perceived as truly useful by those for who they are intended, they will not be innovative. They will be an idea, just changes (that do not necessarily improve what we wanted to change), a different way of doing things, but not an innovation.

The term “acceptance” in the business area refers to the increase in sales of new products and services, as new users acquire them considering that they improve their life and assume the learning effort that is associated with any significant change.(1) We do accept change and we do accept this learning effort because we see the result as an improvement over our previous state. In the field of museums and cultural non-profit organizations, acceptance means increasing the number of visits and participation in social activities of the institution, and also optimizing its new internal processes and management by the workers.

People usually think that innovation belongs to specific departments of organizations that are thought of as innovative or technologic. However, reality has shown that innovation depends on the alignment of all departments involved in the value chain, from the department of direction to the areas that analyze data, from those that generate new ideas to those that communicate or execute changes.

Another topic is that the return on an innovation depends on how big its investment was. Investing part of the budget in new services does not guarantee any achievements or ROI if the investment is not appropriate. Stagnation in museums is usually blamed on their lack of funding. Surely, with more money museums could have started new innovative projects that have been left out of the table because of years of cuts during the financial crisis. In many cases these cuts have affected even the survival of the institutions itself (let alone generating new ideas), but even so the lack of resources should not serve as an excuse forever. After all before the cuts the level of innovation in Catalan museums was not a prominent feature, or at least we can not say that it was in the center of the museum activity.

Money will always be insufficient if we understand it as the sole condition to change things. It is very difficult indeed to innovate without money, but more money does not always translate into better innovation.

Innovation and the Museums Plan 2030What does the Museums Plan 2030 say about innovation?(2) Its wording specifies concrete actions related to innovation in the fields of education (“5.4. Reinforcing the centrality and innovation of educational activities”), social innovation, technological and user experience aspects (“6. Increasing the communication skills of the museum and stimulating its potential to provide quality content and experiences”), and the area of training new profiles (“7.2. Supporting the training and retraining of museum professionals, and also the incorporation of new professional profiles”).

Four basic pillars for running a museum where the ability to improve, change and innovate is put to test.

Staff training in museums is certainly the first step towards change, as only if well trained we will be able to take on new challenges regarding the offer in museums and the necessary digital tools to achieve them. In recent years, university education has been diversifying and specializing in specific areas of digitization and innovation applied to the organization and management of cultural institutions, although it is still a minority.

Incorporating the latest software in an institution is a great economic effort but not an innovation. But designing a globally digitalized institution certainly is. Even though it may seem obvious that our environment must have a strong link with digital technology, not all organizations have implemented digital holistic perspectives. This can be the consequence of a lack of resources or even of the training that is necessary to start thinking of museums as digital entities. Postgraduate training and college courses have come to improve the training of museum staff specially in the areas of management and communication, although there is still a long way to go in training specifically aimed at cultural innovation and digitization. In this regard, the work that the UOC (Open University of Catalonia) has been doing for three years through a specialization course in digital strategies for cultural organizations stands out. It constitutes one of the few specific offers in Catalonia about the digital transformation of museums.(3)

Regarding the new forms of communication in museums, the words “marketing” and “museums” never combined well, or even generated some discomfort. This terminology may continue feeling uncomfortable, but the reality is that the main objective of museums has been redirected towards the public, and this public will not come to the museum by themselves.

Nowadays there are many cultural options to enjoy leisure time with, and we need to address our audience through various marketing strategies. Traditional transactional marketing now shares its space with relationship marketing. The latter aims at getting to know the potential and non-potential audience in depth and with accurate data. It uses their opinion about the offer of the institution, their interests and their new cultural consumption habits in order to provide each kind of public with a more accurate and targeted communication.

A third element that is visibly innovative for museums is the incorporation of digital technologies for the communication of content and user experience. We often speak about technology as a means to achieve a goal beyond screens and algorithms. And we usually use it that way, but sometimes we forget and end up developing technological solutions that actually have little utility for users. In 2019 Xavier Marcet said on change and technology: “Change is how people are able to create more value for their customers or their teams through technology."(4) We should not forget this.

We live in a time in which everything changes quickly, maybe more than we would like. In just a few years our social behavior has changed dramatically because of digital technologies. Words such as artificial intelligence, data mining, robotics, Internet of Everything, mixed and augmented reality, immersive 3D, hyperconnectivity, 5G networks, 3D printing or facial and voice recognition are part of our language now, and they are the technology specializations of the short-term future.

These innovations are the basis of the new industrial revolution that will radically transform the economic relationships between production and consumption systems and change communication systems and the needs and skills to be found in a common workplace. An almost imperceptible apocalyptic vertigo. Because if all these elements have anything in common, that is their condition of being digital, and therefore “invisible.”

The revolution 4.0 is currently present in an important part of the traditional industry, and it is also starting to show up in museums (in some museums). There are many examples to look into, like the AI projects “The Voice of the Art” in the Pinacotheca of the State of São Paulo (https://sites.wpp.com/wppedcream/2017/digital/the-voice-of-art). There IBM ran their Watson software to create a chatbot that responded to questions from visitors. The MAMBA in Buenos Aires also had a robots project called “Dialogue with the Work.” AI was also behind the play “The Last Rembrandt” (https://www.nextrembrandt.com/), where machine learning from billions of data allowed a robot to the create a new painting “by Rembrandt.".(5) These experiences have made us wonder where exactly is the line that separates machines and humans.

Even those characteristics that always defined us as humans (intuition, creativity, the ability to imagine, irony…) are starting to transfer to robotics in projects like “AlphaGo Zero” (how a machine wins a game of intuition), “Artists & Robots” (the Grand Palais in Paris presents works created entirely by robots: https://www.grandpalais.fr/en/event/artists-robots) or “The WHIMSICAL A.I. Project: I’m a Writer” (a literary award in which artificial intelligences can participate and even get to the finals https://shinichihoshi.com/whimsical_ai_project.html).

But do not panic, thus these examples belong only to a small number of museums in the world. These museums have the necessary dimensions and positioning to be able to develop research projects on partnerships with universities and companies from the technology sector. However, the reality of 99% of the museums in the world is still far from that. In the best scenarios technology is applied in many widespread formats such as applications for mobile devices, digitized collections in very high resolution, 3D reconstructions, reproduction of objects and immersive environments, videogames based on museum collections, digital games or immersive audio guides. This offers communication possibilities like never before.

A fourth pillar of innovation in museums of Catalonia focuses on education, certainly one of the fundamental functions of the museum as an institution complementary to formal education programs. The relationship between schools and museums has always been strong and should continue strengthening, as both institution share the same ultimate objective. In recent years the attention of museums has focused on improving accessibility and social participation, designing inclusive activities or developing new audiences (with particular attention to young people). Being already on this track, the big bet for the future is aligning with new educational trends that incorporate learning methodologies and tools, and returning specialized staff to the center of the educational action.(6)

Finally, I will add the term and the consideration of social innovation in museums as a challenge which is yet to develop on the long term. Last years new proposals that combine concepts and techniques of business innovation are under study (Open Innovation, Desing Thinking…) in order to be adopted through the characteristics and objectives of museums and cultural facilities. This translates into new innovative and sustainable projects that follow models like the one from the Museum Model Innovation presented by Haitham Eid in the Conference of Museums and the Web 2016 in Los Angeles.(7) This model proposes a system based on the combination of three elements: the principles of Open Innovation, the creation of business models that make projects sustainable under the principle social enterprises with non-profit purposes, and a model of social innovation focused on prototyping and consolidating ideas in order to design scalable models.

Why don’t Catalan museums innovate even more?What stops Catalan museums to innovate more and in a better way? Leaving aside whether there are or not great financial resources, I propose some reflections on some of the difficulties to set up processes of innovation in museums.

- The model of governance and public ownership. Most of the museums in the Catalan system are publicly owned (87% according to the Museums Plan).(8) In some cases these have reached an amount of bureaucracy so high that makes it very difficult to have a dynamic management regarding many of the processes needed to implement changes. Various criteria (such as contained costs, limited recruitment conditions and hiring systems, and the difficulty in establishing agreements and open relationships) have made administrative processes very complex. Therefore the system has become a machine too big to move smoothly, a machine with a much slower dynamic than the one from private sector initiatives that have greater decision-making autonomy, greater money and also greater risk assimilation.

- Risk and uncertainty, which are inherent in innovation, are other elements that show a difficult coexistence with public administration. Managing public money is a big responsibility and must be an exercise in flawless efficiency. However, innovation involves the risk of failing, having to study modifications, testing, redesigning, rethinking and trying again and again. Innovation requires a continuous process of change and evolution that is hardly compatible with managing public agendas and political responsibilities. Assuming the fact that a new project in which great investment has been made does not work or that it must keep absorbing funds until it does belongs to the business mentality, but hardly to the bureaucratic mentality.

- In the case of large facilities, a certain departmental rigidity remains an internal obstacle too heavy to launch integral, innovative, digital projects because of the compartmented structure of these institutions and despite the theory on innovation as a process that must involve an entire organization. From my perspective, one of the major innovations to be done in the field of museology is optimizing the design of organizational procedures.

- In the case of small facilities, where the previous problems are not that present as a small group of professionals execute all the work in the museum, one of the major drawbacks to innovate is the underfunding of resources (not only economic, but especially human resources). According to the Museums Plan 2030, 57% of registered museums in Catalonia are medium or small (between two and five members of staff). How can the museum staff innovate if they can barely fulfill all their already assigned duties?(9) In this cases, it should be the first priority to increase the human resources, as people can start processes of innovation and creative ideas with little money, while money itself does not think.

These reflections do not intent to mean that there are no interesting innovation processes in Catalonia being developed. However, although the public administration is working to foster and promote innovation processes through the CatLab program (http://catlabs.cat/el-programa/), which aims at articulating the Catalan network of digital, social and collaborative innovation following the model of NESTA (https://www.nesta.org.uk/data-visualisation-and-interactive/helping-innovation-happen/), the truth is that it is still difficulty to implement these processes to the usual dynamics of local public administrations, companies and research centers altogether, precisely because of the difficulty of building long-distance processes with a high degree of uncertainty and a lack of a methodological base of experience. And even though Catalonia is already facing the implementation of the strategies of specialization RIS3CAT, I think this will not affect that much the reality of medium and small museums in the territory.(10)

Where do I find innovation for me?

While museums seek to adapt its organization, activities and objectives to a possible new definition by the ICOM (we’ll see about that), we should ask ourselves about the extent to which museums are relevant to the public in a world where the “competition” in the cultural leisure is becoming increasingly complex. I use this word because, although “competition” is a word that has had a tough acceptance in the cultural sector, it is also the best definition of what keeps the public away from museums. And it is not other museums that integrate the competition, but the new digital channels of information, an increasingly additive cultural audiovisual offer, social behaviors that allow people to learn everything they want just by knowing what they are looking for. It is a society that constantly travels in search of the original object, a wide network of cultural participation, or a society so accustomed to the spectacle that it is becoming increasingly harder to surprise. Given all this, why should the museum still be relevant to the public? What is the math here

The museum collects, preserves, studies, exhibits and disseminates knowledge derived from research of its collections. At first preservation was its most important aspect, turning the museum into the great temple where objects of the past were kept. Then its educational function and the transmission of knowledge were highlighted, and thus it became the temple of knowledge. But nowadays knowledge doesn’t irradiate from a sole place, but runs through the network. Where do we emphasize the word museum now? Being unique and relevant is a fact established based on the scope of each museum, its themes, its collection, its particularity in offline and online communication, its programmed activities and the value proposition of their visits. It does not depend on the size of the museum, but on the strategies they use to differentiate themselves.

From my point of view, museums will only be relevant to society if they go beyond objects and knowledge and ask the relevant questions in today's society.

In the same way that Professor Josep Fontana described the profession of historians as one that has a strong commitment to the present and especially the future. Museums will have an important place in the social context as long as they are engaged with the present and help people understand the world we live in from a determinate context.(11) I think these will be the most innovative museums, because they will be reviewing their narratives, their contents and their stories. This is the great transformation. All other changes and innovations will be subsidiary to this fact: the internal organizational changes, new forms of relationship marketing, attention to different audiences, technological changes focused on experience, educational programs or new communication channels. These will be incremental innovations within the deeper innovation, that consists in what we want to tell today’s world with our collections, our knowledge of the past and the present and our perspective of the context of users.(12)

Three cases of innovation in processes and contentInnovating the content. The renovation project of the Museum of Railways in Catalonia (https://www.museudelferrocarril.org/ca)

It may seem excessive to speak of a disruptive innovation in the renovation project of the Museum of Railways in Catalonia, since the museum has existed for decades and its collection of steam engines is well known (and recognized) in the rail world and railway museums. But to understand the exceptional changes that the museum is going through in recent years, it is necessary to acknowledge two fundamental facts. On the one hand, how are railway museums in Spain and Europe – and on the other hand, what is the history of this museum in the context of museums in Catalonia.

If we can find a thing that most of the Spanish and European train museums have in common without following a thorough analysis of each and every one of them, this is that they were created by railway companies or associations directed by men, engineers and enthusiasts of these machines. A somewhat reductionist vision but a real one, a vision that explains why train museums are as they are. As these vehicles were becoming obsolete they ended up cornered in warehouses and workshops (in the best cases, since most were dismantled), and many collections were created more or less systematically. The passion of railway engineers leaded on to the opening of such museums in which “the machines” took the leading role with no hesitation. They became unwittingly museums of science and technology where the narrative was focused almost exclusively on the technical and scientific explanation of transport systems (steam, diesel, electricity) and operation of railway systems. The power of the machine, the power of the locomotive and the engineering behind each piece were the focus of all narratives. And so they continued like this for years until new issues entered the stories of these museums. Due to changes in society and wider social visions of rail transport, the centers dedicated to trains incorporated new visions just as momentous or even more than the technological changes based on how the railway changed people’s life and the very concept of travel. And it is here we’re this feminine approach comes in to play. And I say feminine because this relationship between train and travel – adventure, stories, inspiration or symbolic component of the rail – is generally more present in women’s imaginary rather than in that of the men who constructed museums.

Today, there are some railway museums that have incorporated these perspectives in their museological and narrative renovations, although they are still a minority in the whole of these centers. Internationally, the cases of the London Transport Museum, which explains how the rail changed society and cities, or the Railway Museum Utrecht (halfway between an amusement park and an educational institution) could be presented as the most paradigmatic ones. However, in Spanish railway museums these issues are still complementary to a narrative that focuses too much on technology.

And here lies the major change proposed by the Museum of Railways in Catalonia – a museographic display that puts the spotlight on the intangible fact of social, economic, and technical changes in train transportation (railway, metro and tram). At the end of the day, this was a technological innovation that changed the lives of thousands of people and world economies over decades, and it now stands at the center of the debate on the sustainability of urban and metropolitan transit in a world struggling between the comfortability of private transportation and the social, environmental and economic benefits of public transportation in today’s increasingly overcrowded cities.

The other fact that explains this new project of this train museum in the city of Vilanova i la Geltrú is its very own history. During its first years of life it was dedicated to a very necessary task for the conservation, management, care and study of one of the largest collections of steam locomotives in Spain. But ten years ago it moved to another stage, now focused on transforming a locomotive depot in a 21st century museum. Towards 2008, museum officials began a profound reflection on their role in society beyond the preservation of the collection that would become the project that we are talking about.

Thus, in this project innovation is to be found in the very DNA of its narrative. The concept of innovation applies to this case not only because of this major change that the museum put into action, but also because of the fact of innovating to change society, the same thing that the railroad did at the time of its birth. And the museum will innovate hand in hand with one of the pieces that best explain innovation: the Talgo II. The history of this vehicle itself is the paradigm of innovation. Without going into further detail about its history – I invite you to go to the museum or to surf the net just to find out about it – let’s just say that its implementation was the most important innovation to the world of trains since its very invention.

In the gray Spain of the postwar, a visionary imagined a train that would change completely the concept of trains. Parting from a definition of trains as ‘a means of transport to take people and goods from one point to another’, he reinvent the concept of travelling itself, and engineers designed for the first time a train in which the passenger and their experience were the most important thing. This radically changed their approach: different materials, new interior designs, comfort, service, technology, colors, security, and so on. Although in one of the first presentations of the drafts someone told its creator Alejandro Goicoechea “this will never be a train,” this vehicle changed forever the way people travelled.

Today, just like when the Talgo II was invented in the 40s, innovation entails risk, dedication, investment, a touch of lunacy and conviction – a blind belief in one’s work to escape the established way thinking and the prevailing logic to improve people’s lives.

This is also the goal of the new project of the Museum of Railways in Catalonia for its new rooms – transforming the narrative and the visitor’s experience dramatically to influence the consciousness of collective transport in an environment that offers an exceptional collection, with a series of transformed spaces designed with new forms of multimedia communication, in order to become an absolute museum of the 21st century.

Innovating the content. The Museum of Rural Life in L’Espluga de Francolí facing challenges as a society (https://museuvidarural.cat/)

One advantage of innovating in the processes of narrative and significative messages reformulation is that this act is not determined by the proximity of the facilities to the major centers that are supposed to be innovative. Innovation is also in the DNA of the Museum of Rural Life in its new stage. This museum shows us how to turn around a more or less traditional ethnological museum to fully update it into the 21st century, and how to do so from outside the environments that are traditionally considered the innovative spaces where just about everything happens: the cities.

For the last year and a half this museum that is property of the Carulla Foundation has launched a new strategic plan designed to position itself locally and internationally, putting sustainability and ecology in the center of its narrative of specialization. That is one of the most important contemporary challenges we face today as a society.

What is the point of having a collection of farming tools in the 21st century? Does it make sense to talk about agricultural knowledge and techniques that disappeared with the industrialization and the mechanization of the agrarian works? Who needs to know about our grandparents’ rural world beyond family memories?

People at the MRL are clear that these are important issues. In our context of energy crisis, climate emergency and estrangement of the natural environment, this museum considers that its present and future cultural narrative must focus on the relationship between people and nature. Resuming and relearning everything that we left behind in the path of industrialization in order to build a new future based on the best solutions to current climate issues. In short, using the knowledge of the rural world preserved in museums to provide solutions to challenges that are global in today’s world.

This is certainly a big change of narrative, and probably the most important innovation in the lifetime of the MRL in comparison to its previous trajectory. The role of the museum and its program of activities is to claim equity between the countryside and the urban environments – in fact, even during the surges of its cities, Catalonia never ceased to have a rural environment that made possible the rise of its capitals – to become a reference space in global and local issues of sustainability and climate emergency, and to do so with a contemporary cultural language. Therefore, one of the key issues to this project is the creation of local networks with the immediate and the national environments, as well as establishing distant strategic networks with other international centers.

Returning to my first reflections, the biggest challenge that these facilities will face in the future is not only to reinvent themselves and to innovate as museums in their respective narratives, but to do so all together with other institutions and organizations involved in a social and shared change in progress. The project will be successful only to the extent that all organizations incorporate this idea. And so, spreading it will be the next step of the process.

The MRL sought inspiration in historical models to try and take another step forward. It took some ideas expressed and developed since the 70s in the ecomuseums in Switzerland and France – models that understood the concept of a museum as a territory or community that has to be preserved – or even in American or Canadian museums that aimed at the preservation of the culture and environments of indigenous peoples. The MRL adds its role as a creator of knowledge to the conservative function.

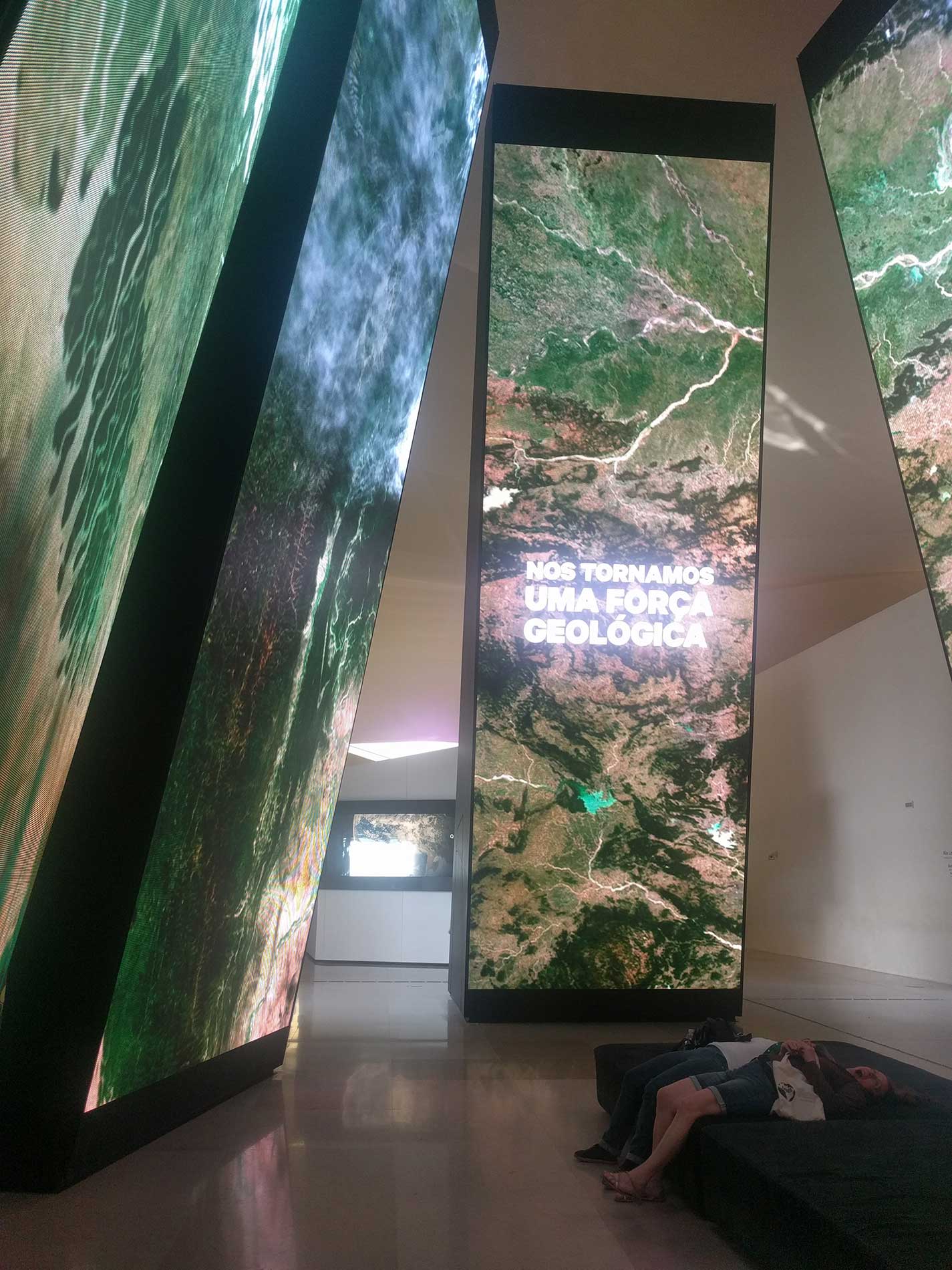

The museum presents itself as a meeting point for specialized research, for its target communities and for the creative world that offers new formats to communicate contents. The museum is a place for new questions and for possible new answers to global problems. It is not a sealed off system of absolute answers but a place to exchange knowledge and to seek new solutions. The Museum of Tomorrow in Rio de Janeiro (https://museudoamanha.org.br/) is another one of the benchmark institutions for the MRL. With a classic structure of “where do we come from and where are we going to,” it addresses us about how the current behavior towards our environment has become for the first time in history a modifying agent to the conditions of the planet, and about what we are willing to do in order to build our future. A museum with a strong contemporary narrative that was carried away by technological innovation far too much, maybe because of its starting conditions.

The MRL just started walking the path that in the coming months and years will develop its whole cross-network strategy that aims at education, communication, tourism and reflection centers: a new educational project, already underway, linked with UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goals especially in terms of food, energy and water; a new program of activities linked to the narrative of the museum; a program of temporary exhibitions that constantly updates its contents; and a new permanent museological proposal.

Innovating the processes. The Ter Museum in Manlleu and participation (https://www.museudelter.cat/)

The last example presents us a topic of great interest and debate today – people’s participation in its daily activities. Within the internal work dynamics and the effort in connecting with their audiences, museums have been trying for quite some time now new ways to be seen as social spaces of collective creation. In the case of the Ter Museum – and many other museums in the region – public participation has been the basis of its positioning because of the fact that local people are the main users of its facility.

Its construction as a meeting place for groups and organizations of the region has allowed the museum to achieve both good quantitative goals – a very creditable figure of 26,391 users in 2018(13) – and qualitative objectives through their conception of the museum’s work as a connector of research projects, activities, new communication languages and pretty much the whole the task of weaving a network with its social and educational reality.

Far from tourist routes and environments saturated with visitors, the Ter Museum is the main space to get to know a less known part of the history of the Osona region. Traditionally related to agriculture and livestock economy, this territory played a significant role in the industrial history of Catalonia. The industrial building that houses the museum, called Can Sanglas, can not be understood without everything that surrounds it – the river, the land, the people – and in the same way the museum itself can not be understood without the set of relationships woven over fifteen years with local schools, groups of newcomers, research centers and the University of Vic.

Getting more than twenty-six thousand users in an industrial museum outside the usual circuits is indeed not easy. But it succeeds in doing so precisely because of this close relationship with its environment, enabling everyone to feel the museum as an open space in which to develop projects and to meet with other groups. And it also succeeds in doing so because its direction understood that people feel that the museum is their own space only to the extent that they feel represented by it. The museum got to be the agora of local social groups such as the elderly, the newly-arrived communities, associations and organizations, schools, professionals of the historical and natural heritage sector. It opened its door to internal but also external research projects, to local heritage projects, to artistic creation initiatives that integrated into the museum's collection, to projects aimed at recovering the orchards of the local factory, to projects invested in new visual formats, and so on.

I want to highlight particularly two elements of connection with the audience. On the one hand, the theatrical project carried out for ten years by the museum in collaboration with the theater company CorCia, in which they use theatrical language as a means to communicate and give life to local history, reinforcing the close relationship that theater culture had with the working population in town. Every summer, the company designs a new play based on a true or prominent story of Manlleu and the collective history of Catalonia – old cinema, the historic workers' cooperative, the first democratic elections, the Civil War or the importance of women in the industrial world. This format has been consolidating throughout this time, and it has gone far beyond the museum's walls to become also a link with the Institute of the Ter through the Magnet program, which transforms students into lead actors of the cooperative while also making us reflect on the reality of the industrial world.

On the other hand, I want too highlight the project “Revealing Historical Memory” too, which is focused on local visual memory in collaboration with local organizations. It invites us to use photography as a historical resource and a object of exhibition.

One final piece of advice – do not go to the museum during the Museums Night because it is closed. How come? Because the Ter Museum offers the possibility of entering many other nights during the year in which many activities are programmed. This is also innovative!

Acknowledgments:

Gemma Carbó, Director of the Museum of Rural Life.

Pilar Garcia, Director of the Museum of Railways in Catalonia.

Carlos Garcia, Director of the Ter Museum.

Notes

BARBA, E. (2011). Innovación, 100 consejos para inspirarla y gestionarla, Barcelona: Libros de Cabecera.

BARBA, E. (2011). Innovación, 100 consejos para inspirarla y gestionarla, Barcelona: Libros de Cabecera.

I invite you to read Concha Rodà in the blog of the MNAC on other international and Catalan examples (available at: https://blog.museunacional.cat/experiencies-digitals-per-connectar-amb-els-visitants-de-museus/) or to visit the content of the MuseumNext (available at: https://www.museumnext.com/article/10-startups-disrupting-museums/).

I invite you to read Concha Rodà in the blog of the MNAC on other international and Catalan examples (available at: https://blog.museunacional.cat/experiencies-digitals-per-connectar-amb-els-visitants-de-museus/) or to visit the content of the MuseumNext (available at: https://www.museumnext.com/article/10-startups-disrupting-museums/).

On the work done in relation to education and museums in Catalonia, please refer to the Conference of Museums and Education organized by the Maritime Museum since 1995 that has been institutionalized as a national reference on these issues. On the situation of the teaching staff in museums, just taking a look at the press in recent years gives an idea of the precarious situation that surrounds this group, partly because of outsourcing services under conditions that are totally insufficient.

On the work done in relation to education and museums in Catalonia, please refer to the Conference of Museums and Education organized by the Maritime Museum since 1995 that has been institutionalized as a national reference on these issues. On the situation of the teaching staff in museums, just taking a look at the press in recent years gives an idea of the precarious situation that surrounds this group, partly because of outsourcing services under conditions that are totally insufficient.

Museums 2030. Museums Plan of Catalonia (2017), Government of Catalonia, Department of Culture, p. 37.

Museums 2030. Museums Plan of Catalonia (2017), Government of Catalonia, Department of Culture, p. 37.

Please refer to the suggested work from the area of work on the equipment of museums, from the Forum of Museums of Catalonia (available at: https://cultura.gencat.cat/ca/temes/museus/forum-dels-museus-de-catalunya/primer-forum-dels-museus-de-catalunya/forum_tancament/).

Please refer to the suggested work from the area of work on the equipment of museums, from the Forum of Museums of Catalonia (available at: https://cultura.gencat.cat/ca/temes/museus/forum-dels-museus-de-catalunya/primer-forum-dels-museus-de-catalunya/forum_tancament/).

On the importance of the personal and cultural context of the users, please refer to the work of Jonh Folk and his Context Model of Learning (available at: ‘Enhancing visitor interaction and learning with mobile technologies’ in “Digital Techologies and the museum experience” (2008) Ed. Loïc Tallon and Kevin Walker, Altamira Press, p. 19-33). Falk, J. (2009) “Identity and the museum visitor experience”, Left Coast Press.

On the importance of the personal and cultural context of the users, please refer to the work of Jonh Folk and his Context Model of Learning (available at: ‘Enhancing visitor interaction and learning with mobile technologies’ in “Digital Techologies and the museum experience” (2008) Ed. Loïc Tallon and Kevin Walker, Altamira Press, p. 19-33). Falk, J. (2009) “Identity and the museum visitor experience”, Left Coast Press.

In this sense, and in the line of transformation in which museums are involved, the ICOM proposed “Museums as Cultural Nuclei: The Future of Tradition” as the theme of the International Museums Day 2019. They pointed out the active role that museums play in their communities, oriented to global issues and conflicts from their local perspectives with the participation of their audience.

In this sense, and in the line of transformation in which museums are involved, the ICOM proposed “Museums as Cultural Nuclei: The Future of Tradition” as the theme of the International Museums Day 2019. They pointed out the active role that museums play in their communities, oriented to global issues and conflicts from their local perspectives with the participation of their audience.

According the Memory of the Ter Museum, 2018 (available at: https://images.museudelter.cat/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/MuseudelTer_memoria_2018.pdf 2018).

According the Memory of the Ter Museum, 2018 (available at: https://images.museudelter.cat/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/MuseudelTer_memoria_2018.pdf 2018).

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY

MNEMÒSINE REGISTRY